Illustrations by Dan Turner, Designed by Loid Der

Seven Stories Press, 2008

7.5 x 5.25 (19 x 13 cm)

Perfect bound softcover

ISBN 978-1-58322-780-0

Photo: Carla Liesching

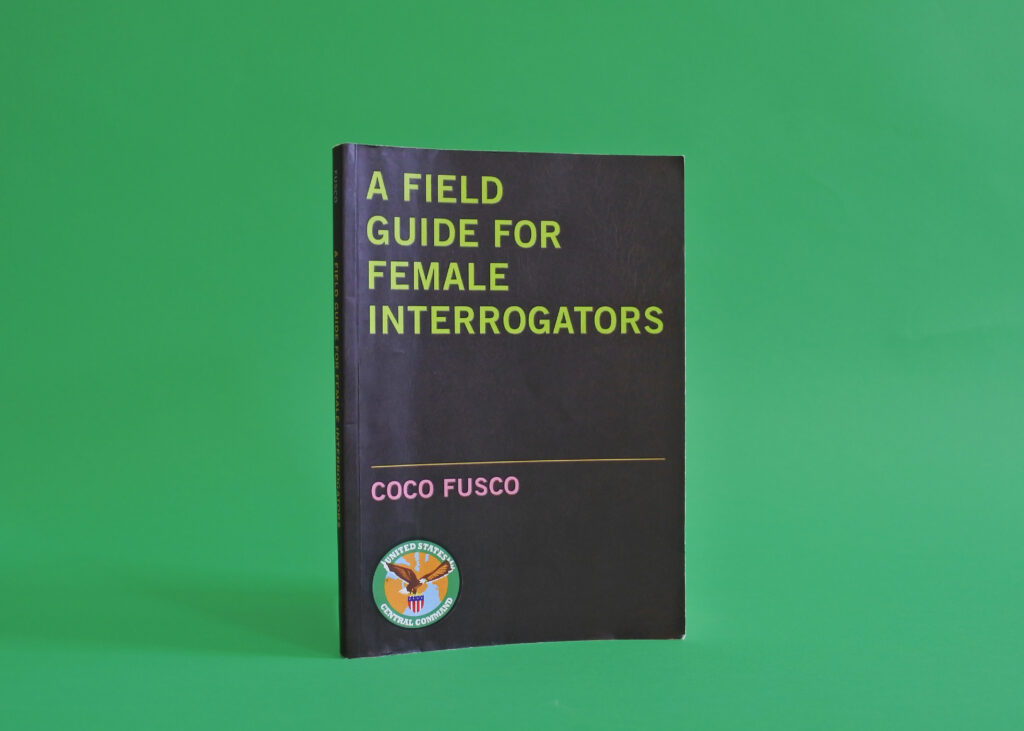

Coco Fusco’s A Field Guide for Female Interrogators is designed to reference a CIA manual. With a bold fluorescent-green title—all-caps sans-serif font, printed on a fake-leather background—the cover is a reasonable facsimile demanding attention. Below Fusco’s name in pink is a circle containing an image of an eagle and a flag. The colorful logo reads, “United States Central Command.” The light, thin book promises to unsettle, as well as to entice, fool, and play with the reader. It’s a piece that stands out among the collection at Center for Book Arts, not only thanks to its compelling cover, but also because its confrontational imagery makes it hard to ignore. A Field Guide—and its unique place in the CBA archive—invites readers to reconsider the significance of book art as political and social critique, the role of archivists in shaping knowledge, and the transformative power of publishing and printed matter.

While Fusco’s book was published in 2008, this is an apt time to revisit her work: January 2025 marked twenty-three years since the Guantánamo Bay prison has been open, and of the fifteen men still detained and ensnared by bureaucratic inaction and politics, six have never been charged. On the heels of the transition of power to the new administration, President Trump announced an executive order to prepare a massive facility at Guantánamo to detain immigrants, collapsing the global signs of US-sanctioned lawlessness and racism into one.

Rooted in her experience growing up with a mother exiled from Cuba, Coco Fusco’s artistic career has often examined the relationships between the body in performance and the greater body politic of a state—notably in Cuba, where the state defines itself as revolutionary but also seeks to limit dissent. A Field Guide for Female Interrogators, made in response to the images that emerged from the US-controlled prison in Abu Ghraib, Iraq, follows this line of inquiry. In this illustrated how-to manual, Fusco performs the tragically racist, xenophobic, and anti-Muslim sentiment that Guantánamo’s existence continues to perpetuate: She leads the reader through the step-by-step process of how CIA officers conduct interrogations. The officers are staged as mostly white and female; the detainees are represented by a tragically silent or openly raging prisoner, who is always blindfolded. Where violence, gender, and female sexuality serve as a thematic anchor for the performative acts of both making and experiencing the book, Fusco offers us a counter-manual—one that rejects, through its (re)performance, the actual CIA torture manual developed in secrecy toward a nationalist, racist emblem of state power. Her book evokes the ways gendered violence plays out in state legislation and training for military officers who conduct torture, sketching the escalation of “stress positions,” sound-as-weapon, starvation, and intimidation tactics that capitalize on cultural and sexual phobias. Here, as through the entire book, the artist lays bare the pointed and controlled mechanisms through which subjugated people are stripped of their agency.

In exposing the way the state conducted torture in Abu Ghraib, Fusco delivers disturbingly playful images and instructions to demonstrate how women in the military are sexualized and objectified, but also trained to uphold the apparatus of a sexualized and gendered economy of violence. Fusco shared with me, “The book is a response to Virginia Woolf's Three Guineas”—a book-length essay published in 1938. “Virginia Woolf asks how women can stop war, and I write about how women [are] engaging in war.”

Photo and artwork: © 2025

Coco Fusco / Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York

Photo and artwork: © 2025

Coco Fusco / Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York

A Field Guide draws on Fusco’s research and the scripts she compiled for two projects between 2005 and 2009: her performance piece A Room of One’s Own: Women and Power in the New America and her film Operation Atropos, both of which were selected for the 2008 Whitney Biennial. Her performance A Bare Life Study premiered in the Brazil Festival of Electronic Art and Performance in September 2005.

Combining art projects with critical commentary, A Field Guide meditates on the role of women in the “War on Terror” and explores how female sexuality is used as a weapon. Fusco also points to an unspoken function of war: the performance of violence as an experience of pleasure for the performer.

At once a too-real instruction manual and a sadistic mockery in its form, A Field Guide presents archival material, collapsing dynamic layers of violence and power with many valences of texturally rich, imaginatively deployed references and sketches. It also aggregates Fusco’s own personal experience enrolling in a military training course, breathing new—and unsettling—life into dominant modes of knowledge production. Blank pages offer brief breathing space from the overwhelming and repeated theaters of violence. The book becomes a mirror, providing a texture and a colorway to the interrogation room, the detention center, the prison cell. In allowing the reader to experience this cruel logic through her palette, Fusco engages the question of how violence brought on by the state is viewed: While the scenes are not for the public, they’re still emblematic of the state’s use of violence and its view of how it operates (in this case, where accountability for torture is absent).

The book is divided into four parts. The first section, “Invasion of Space by a Female,” is about 100 pages and consists of a personalized letter to Virginia Woolf. Fusco’s tone is harsh and direct: “unlike you, I’m resigned to the persistence of war.” The letter reveals her stakes in conducting the research: “I lost a brother who joined the Special Forces and was killed in a covert mission in the 1980s … and then I watched the military do everything possible to hide the circumstances.”

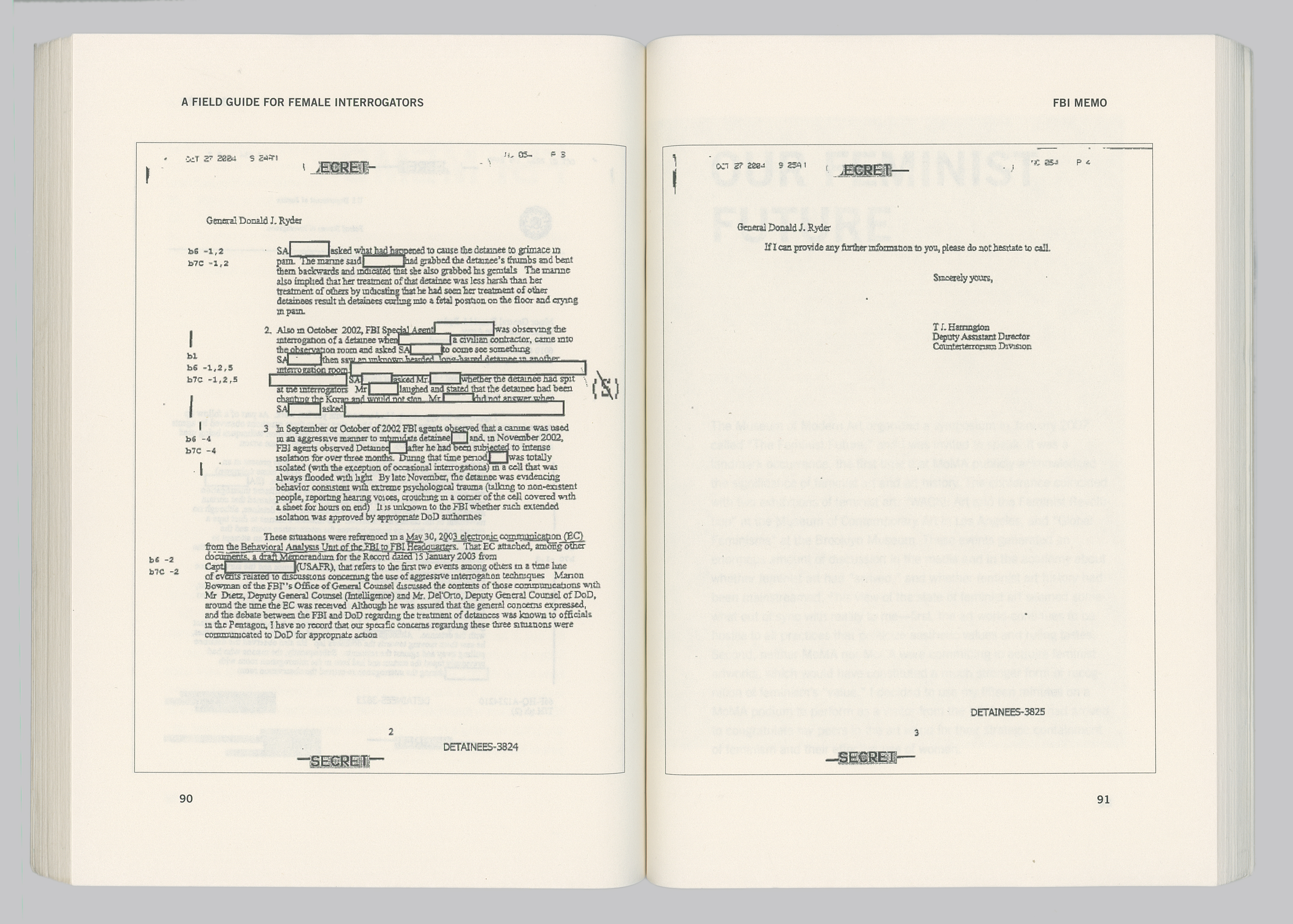

Fusco also lays out her research process. In order to engage with military interrogators directly, she posed as a student in a verifiable interrogation course run by Team Delta. Using details drawn from actual accounts, Fusco conceives a series of drawings that prompt questions regarding state torture. The Field Guide itself doesn’t begin until page 107, and not before a xeroxed FBI memo, which provides the first visual break from Fusco’s long letter to Woolf. It’s a 3-page letter from an FBI agent titled “Re: Suspect of Mistreatment.” Many of the words are obstructed, but the scratches, smudges, and imprints in the text give shape and texture to the authoritative black-and-white document. “Secret” reads at the top, the S blurred out. Scattered phrases display: “the detainee was shackled and his wrists cuffed” and “whispering in his ear and caressing and applying lotion to his arms [during] Ramadan.” Much of the lettering is crowded together, with blocks of letters and entire words in the paragraph whited out. Preceding the memo, Fusco contextualizes what we’re looking at: “[The] following FBI memo from 2004 contains a description of an interrogation that an agent observed in late 2002 involving a female interrogator who made sexual advances as part of her approach to a prisoner.” Here, Fusco exploits the truth claims of documentary practice only to explore how truth gets buried.

Photo: Carla Liesching

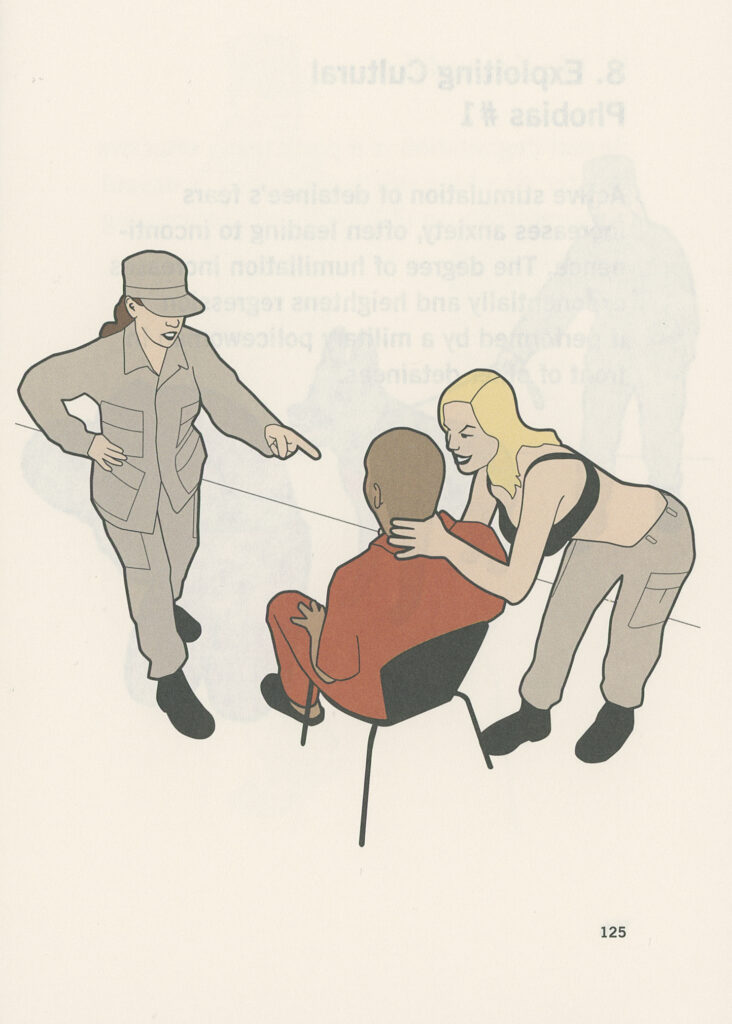

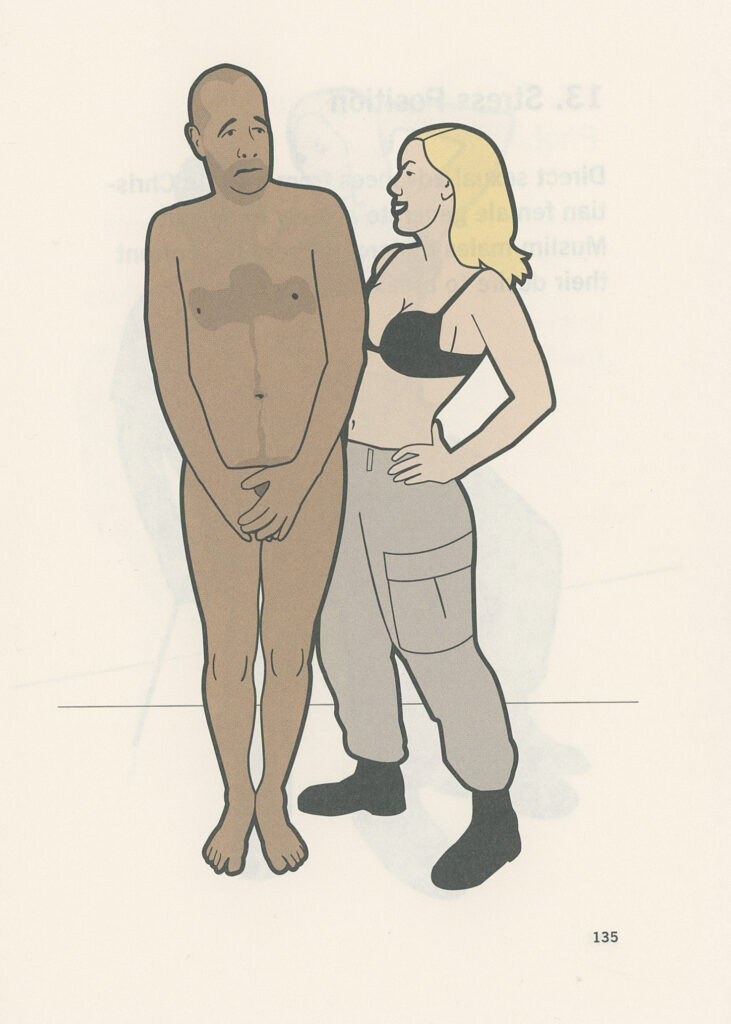

The final section—the actual field guide—is made up of sixteen cartoon drawings, each image accompanied by how-to steps. The cartoons, by artist Dan Turner, illustrate the sexual tactics reported. The figures of half-dressed officers and orange-jumpsuit-clad detainees repeat themselves in nearly exact copies of each other. The detainee is depicted as a brown-skinned bald figure. In most of the images, he’s handcuffed. In a bleak, plain white room, Fusco repeatedly delivers scenes of violence: force-feeding pork on important religious days, starvation, a speaker amplifying noise beyond human tolerance, a nonconsensual lap dance. Fusco’s titles for the how-to steps in the accompanying essay “Our Feminist Future” are satirical and mocking: “STEP 6: TOUCHY FEELY DOES IT EVERY TIME.”

Coco Fusco, A Field Guide for Female Interrogators, 2008

Photos: Carla Liesching

Coco Fusco, A Field Guide for Female Interrogators, 2008

Photos: Carla Liesching

Coco Fusco, A Field Guide for Female Interrogators, 2008

Photos: Carla Liesching

Moving through the book, interrogation tactics increase in severity. In each of the steps, Turner’s cartoons are concerned with the figure in its most basic form, caricatures devoid of real human presence. Drawings make familiar racial and gendered references integral to the experience of looking—white female officers, one brown man—and readers begin to sense that race and gender are easily knowable and categorizable. Fusco’s satirical and subversive titling delivers disquieting links between pleasure and violence. As the reader progresses toward the end of the guide, questions become unavoidable: What are we being instructed, or asked, to do? Are we onlookers, or participants in the brutality laid out on the pages?

At the end, the final step is titled “Fear Up, Harsh.” The text on the left-hand side reads in bold font:

This tactic is so inflammatory that it should be reserved only for the most resistant sources. There is no way to resume a normal exchange after the severe emotional crisis that it is likely to generate.

The image accompanying the text portrays an officer with long blond hair in military cargo pants and a black bra. She’s standing over the detainee, who is screaming. His face is coated with streaks of blood that the drawing indicates the officer has pulled from beneath her own underwear. The book ends here, abruptly, leaving us on this final bloody page.

The most probing aspect of Fusco’s practice—the ability to dig at discomforts, which knows no limit—creates an experience, or a spectacle, executed to wild precision. A Field Guide is at once so declarative and on the nose that it forgets pathos.

Due to such troubling imagery, it isn’t an easy book to grapple with. Thus, speaking with Gillian Lee, librarian at Center for Book Arts, offers a glimpse into Fusco’s work as part of a longer tradition of book art’s role in social critique and knowledge production. In tracing the journey of A Field Guide to CBA, it becomes clear how book art criticism plays a role in exposing hidden historical accounts of state violence, and how book art may counter omitted or problematic narratives in the public imagination.

Taking up Fusco’s book with Lee, I was given the opportunity to enter the information economy with expert guidance, enhancing my ability to make sense of print and visual culture and the history of the book—practices that are critical to public discourse, but often guarded by elite forms of knowledge dissemination.

The presence of Fusco’s book at CBA is instructive—it is an artifact of a larger performance carried out by Fusco as an artist, and at the same time it is an artifact of the greater political situation Fusco was working within, making it ever more important that the book is findable and accessible.

LS: Tell me a little bit about how you first encountered Coco Fusco’s book. What were your impressions of it when you first handled it?

GL: We keep more than one book in each of the archival boxes in our collections. Books are grouped by size and boxed together in the order in which they are catalogued. Fusco’s book is in box 62—when I open that box to pull other books, I notice it because her work looks different from any other book in the box. On the cover the title is pretty big and high contrast; it contains the word interrogators; and it’s printed to look like leather with a fake leather grain. You can also tell from its sheen that it’s a mass-produced paperback. In a collection of mostly handmade books it immediately catches my attention. It’s notable when there’s a commercially printed book in the collection—it says that the content is something to pay more attention to.

Within box 62, there are poetry chapbooks, books on fabric. Chapbooks get requested a lot, so I open it a lot. I opened A Field Guide and flipped through it. It’s a field guide, so it quite plainly describes interrogation techniques. It makes me feel bodily uncomfortable—so it’s a weird piece to sit down with for a little while. The beginning seems to be written by the artist, and then 85 pages in there's an FBI memo. At 107 is where the actual field guide begins. Then, it’s cartoons that are difficult to look at.

LS: What do you know of how CBA acquired Fusco’s work?

GL: Our collections mostly grow through donations. We either receive larger, generous donations from collectors or receive books one at a time, donated by publishers and artists. Since we only have a small budget for acquisitions, we purchase infrequently. A Field Guide is one of the rare ones that we purchased—directly from the publisher, when it was shown in an exhibition held at CBA in fall 2016, Enacting Text: Performing with Words.

LS: How may your role as a librarian shape the larger field of book art criticism? What role would you say librarians play in book art criticism?

GL: Because I’m here in the collections room every day, I am simply more familiar with the extent of what we hold. So I can lead researchers to works they may be interested in if they don’t know exactly what they’re looking for. And I do have my biases—all librarians do. Different librarians have different opinions. As a result, I definitely focus on certain kinds of works and works by certain kinds of people. So I say that I’m more intimately acquainted with the collections than your average researcher because I’m here every day, and that is certainly true, but perhaps more accurate to say would be that I am especially intimately acquainted with certain areas within the collections because they are of particular interest to me, because of my background and tastes. For all of these reasons, I, in my own way—like any of CBA’s librarians past and like any librarian at a small special collection—can shape the larger field of book art criticism simply because of what I pay attention to. I do take that responsibility seriously; my role is not to be an interpreter of work, but rather it’s to be a steward—to house them safely so they will be available to future researchers. But it would be irresponsible to suggest that I don’t—that all librarians don’t—have biases, have taste, have a background informing my decisions.

With A Field Guide, or any book in the collection, I have a descriptive role, meaning my job is to catalogue the book in the database, or retrieve the book based on the description in the database. Cataloguing does involve interpretation: When you’re trying to assign subjects to books, you have to interpret their contents. This book, for example, describes methods of torture. In looking at the book’s record, I found that it had at a previous point been catalogued with language that surprised me. The subject headings assigned to the book were: artists’ books, feminism, gender issues, military prisons, sex role, soldiers, terrorism, and torturing.

Usually, subject headings aren’t so detailed. At CBA, when cataloguing, we have the option of either assigning our own subject headings or “copy cataloguing,” just copying what other art institutions have done to catalogue the book. Because of a quirk of our database, we use Getty AAT more than Library of Congress subject headings. “Torturing” is a subject heading from the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus. You can assign a Getty subject if the work depicts or is described by the subject heading. Fusco’s book depicts torture … or “torturing.” MoMA’s library assigns the following Library of Congress Subject Headings to the book: Women -- United States; Military interrogation -- United States; Women -- Sexual behavior; Abu Ghraib Prison; Women and war -- United States; Iraq War, 2003-2011 -- Prisoners and prisons, American; Women soldiers.

LS: When you generally first receive a book, what is your process in looking at it? Touch, font, bind, size—what do you pay attention to?

GL: I initially do a very surface-level information gathering: title, author, date that we received it, and where it is. It’s called an acquisition record before it's catalogued. We write down information, OPAC—online publicly accessible catalogue, the library database website. Cataloguing artists’ books is a challenge that librarians face because it’s not completely standardized. Here, we lean towards describing in the notes field. It’s complicated because there’s so many different criteria that our patron base searches for. We have such a specific set of users: arts, art historians, instructors. So how can we make our books as findable as possible?

How a piece of art like Coco Fusco’s moves, in the fullness of her multipart performance, to the reader of a certain context at CBA exemplifies the need for political artists like Fusco to become more accessible—and cited, discussed, studied. Given that so much of our knowledge from the past comes from archives created by those with power, interlocutors and librarians not only help translate but can also make it possible to come across illegible, difficult texts. In our age, media and visual images take on a role that continues to be central in the development of our political and intimate lives. Further, at this particular moment, librarians are under threat in the United States. Yet interactions with librarians may very well be an important starting point in understanding the ways that media surrounds us and shapes our understanding of the world.

In this instance, through discussing the text with Lee, a steward of book art, the process of engaging with Fusco’s work becomes relational—and this is perhaps the only way to engage at all. The form of Fusco’s Field Guide forces the reader to grapple with how we, as citizens, consume state-produced violence, asking, at the same time, whether art can inspire renewed possibilities toward creative methodologies to imagine futurities and genealogies of life beyond the state.