“Poetry is the reader’s encounter with the book,” said Jorge Luis Borges at a conference at the Teatro Coliseo de Buenos Aires in 1977. This also applies, perhaps even more so, to the photobook format. There is an almost preternatural quality to reading a photobook, found in the pleasure, the puzzle, adapting one’s breathing, heightening one’s sense of smell, touch, even sound. Reading it enlists our whole bodies.

For Alejandro Jodorowsky, poetry is an act. We believe photobook reading constitutes such an act, becoming poetic when the book breaks with what we expect that book to be, making us see through different eyes. The flexibility or rigidity of a cover, methods of binding or stitching, typography, paper weight, texture, ink choices: All this and more is at work in a photobook, turning what is logical into the illogical, unanticipated, contradictory, and wonderful.

Reading a photobook is an invitation to enter the universe of an author through a complex system and architecture. Sequences beat with a certain rhythm, creating new images and unveiling new stories through editing and design. A visual arrangement enlists our eyes and minds to draw a whole out of a series of fragments and pieces. In this sense, a sequence offers endless possible associations. But there are some that potentialize the inner force of each individual image, creating either tension or softness between them, establishing a complex and sensitive conversation in the interstice. Reading here becomes a matter of letting one’s sense of self give in to other senses. The subtleties and the silences are revealed only if the reader is perceptive enough to comprehend the many layers of a photobook’s images, texts, even empty pages. Everything matters in a photobook: what is visible and what is invisible (or barely suggested).

To read a photobook we need to touch it with our eyes. We need to develop what Gilles Deleuze calls “a new clarity that comes from the formation of a third eye, a haptic eye, a haptic vision of the eye.” When we “read” images that have been printed and arranged in a book, we’re also using the sense of touch, and therefore we develop a haptic visuality that implies “an intimate form of looking, where meaning is formed with the graze of the eye over an object.”

But what can it mean to see images through touch, to caress objects with the eye?

Looking at the experience of reading, we turned to several photobooks, considering all decisions made by the photographers, designers, and publishers as possible clues as to how works might challenge our understanding of the form, activating our sensations and feelings such that the poetic act is made tangible. And here is where our Latin American photobooks start to become important. For over three years, we looked at Latin American books, wondering whether books that dealt with subjects such as migration, political persecution, social upheaval, gender inequity, deforestation, Indigenous displacement, and all kinds of unfathomable loss could be imbued with the same poetic potential Borges saw in literature.

With time, we realized the “act” or “encounter” seemed to be situated in the way the reader had to relate to the work physically in order to understand it. This formed a foundation for the long and dedicated research project that became the exhibition Photobook Universe: Printed Constellations in Latin America. The exhibition was situated in Madrid, where people could explore the books gathered and organized by the physical gestures necessary to read them

Why make such a curatorial choice? Is it so important to explore the way touch activates a new kind of reading?

We firmly believe so. The craft of making the book is as relevant as its content. Each reading invitation has been carefully designed and implemented by its publisher to support the reception of these books. By allowing people to find a calm and cozy environment to read, letting them touch and even play with the books, we were offering the opportunity to consider the nuances of manufacturing decisions. Why would a photographer or designer make a reader break some pages to see what is inside? Why make a reader unfold double pages of a book so that a simple sequence multiplies into a complicated one? Or even: Why do some photobooks tell a nonstory, an illegible story?

To address these books, we decided to use “action words” to represent particular physical gestures that initiate meaning in a book. These kinds of gestures (and there are many) are performative acts that need further examination.

Although we introduced a list of other verbs and actions to guide our public into an exhibition at Fiebre Photobook in Madrid in 2022, here, for today’s reading session, we use the action word:

To Unfold

Looking at hundreds of Latin American photobooks, we noticed publishers, photographers, and designers often employed the physical act of unfolding as an essential element to the conceptual understanding of the book. In other words, for the book to become intelligible, it was necessary that the reader perform a specific action: unfolding. A third dimension appeared in these books. Photographs could become moving sculptures and create a sense of place in two-dimensional print.

Hand printed and bound, 2014.

6 x 157.5 in (15 x 400 cm), 3 pages.

Edition of 100. Box will 3 photograms, printed on

cotton photographic paper, wound up in scrolls.

© Roberto Huarcaya

Amazogramas

The book Amazogramas by Peruvian photographer Roberto Huarcaya opens as an object containing three photograms. The original photograms come from a series of large-format photographs taken in Madre de Dios, in an area called Bahuaja-Sonene, in the Peruvian Amazon. They are monumental pieces, made with a 30-meter-long sheet of photosensitive paper supported on a succession of bamboo sticks nailed to the ground and held by a ribbon. To make the prints, Huarcaya enters the forest at nightfall, stretching the paper out and allowing the delicate light to travel through the jungle to record silhouettes of tree trunks and leaves. These huge Amazogramas (a combination of “Amazonas” and “photogram”) recall the idea of a footprint. The trace of light and shadow left when light brushes against the paper is then developed with river water, collected and carried to a big tent constructed with the help of the Ese'Eja, a local indigenous community.

The striking thing about the book is that, in order to read it, it is necessary to take at least the first two rolls of paper out of the wooden base and unroll them from side to side. The act of reading becomes poetic because reading here is made strange, activating the desire to contemplate the landscape with greater attention. The Amazon reveals itself little by little without any disruption, pointing toward that inexhaustible extension of trees, vines, bushes, and moss. The black-and-white silhouettes of the jungle, engraved on photosensitive paper in the late hours of the night, become a composition of graphic imprints, black vegetable shadows on soft paper.

Seeking to repeat the viewer’s experience with the enormous original piece—a photogram of a forest that we can’t see, portrayed entirely without having to take thirty steps to cover the 30 meters of space it occupies—Huarcaya decided to produce this book, published in an edition of 100 copies. Amazogramas, the book, is a small black box containing delicate art pieces: three rolled pictures measuring 4 m x 15 cm, containing large and uninterrupted photograms of the Amazonian forest.

There is a video, made by El Centro de la Imagen in Lima, Peru, where you can see why reading this book implies a performance. This book asks us to actively contemplate the value of this vast territory and why the Ese'Eja ethnic group aims to live in balance with its natural forces, treating the forest with a sense of sacredness and admiration.

In Amazogramas, the image remains a fragment of a complete ecosystem. What remains of the imprint is the register, a silent mark that invites us to participate in this delicate ritual, seeing the Amazon without touching it, without damaging anything.

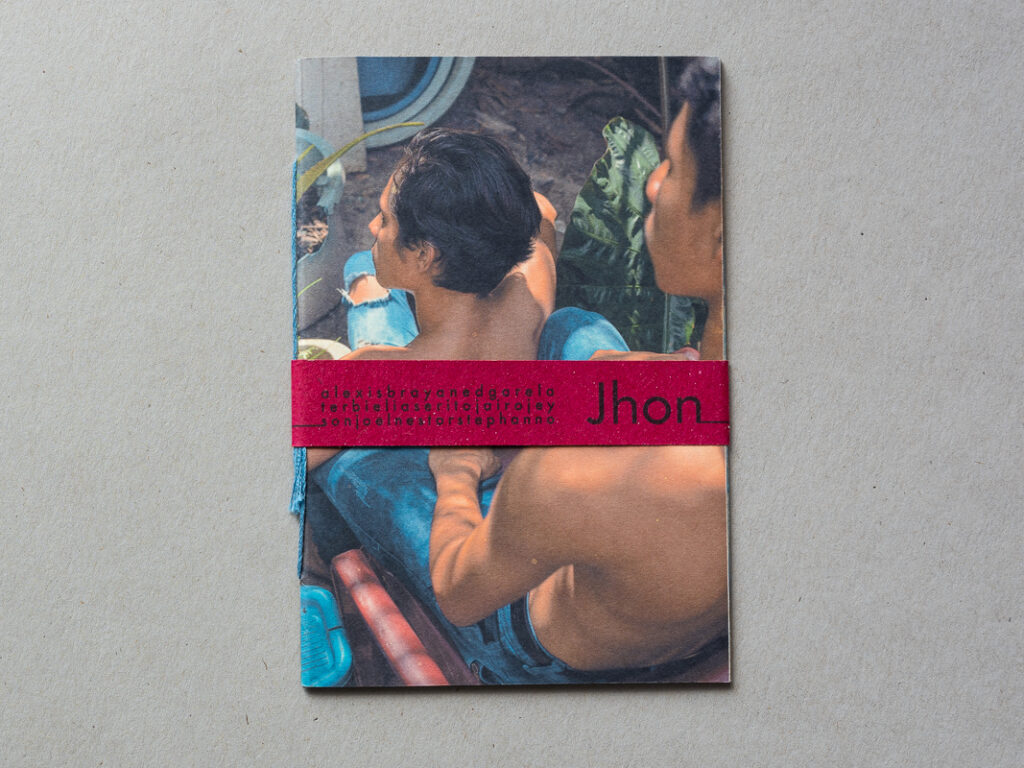

Jhon

Ibanez and edited by Caio Siqueira.

Editora Fotolab Linaibah, 2019. Edition of 30.

Inkjet printed on 120-gram Fedrigoni paper.

© Thomas Locke Hobbs

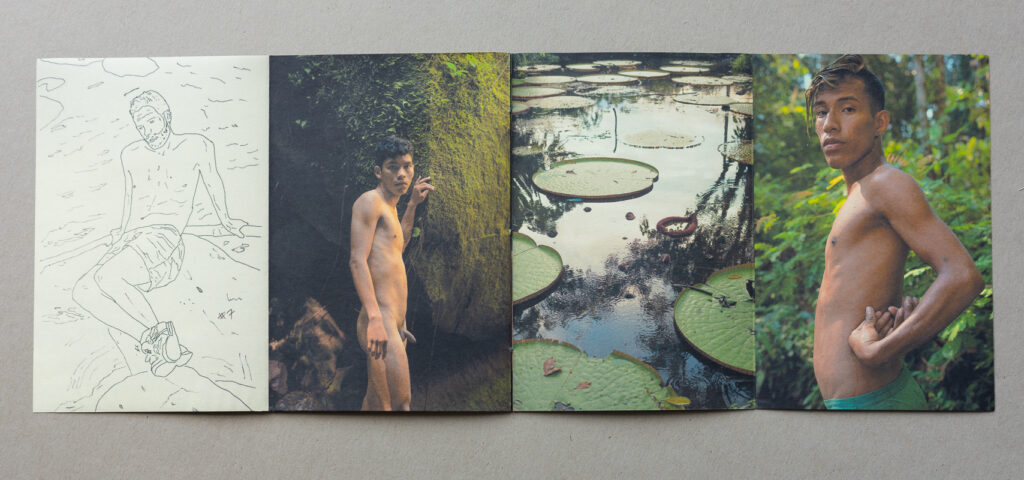

Our second photobook is called Jhon, and it is an equally rare work. Published in the form of a fanzine by Thomas Locke Hobbs, an American photographer, and Lina Ibáñez, a Brazilian designer and founder of Fotolab Linaibah, an experimental book platform based in São Paulo, this small publication fits in the palm of one’s hand. It was produced with a mechanism of double pages that the reader can unfold outward, so that when you turn each page, two images are revealed, and hiding in the interior are four other images that you can choose to unfold or not. In this small format, the publisher and photographer conceived of a way for readers to see two, three, or four images in sequence, depending on how they fold and unfold the pages.

Everything is delicate and soft in this book: the small format, the careful craftsmanship of the printing, the pastel tones of the photographs, and the matte surface of the paper. To make this book, Locke Hobbs and Ibáñez collaborated with editor Caio Siqueira, creating the final form. The most striking thing about this fragile book, made with about 20 pages and published in no more than 30 copies, is that there is space to approach, get to know, and discover Jhon, a model who blends in with the landscape of various places in the Peruvian Amazon. At the end of the book—no matter how many times we go back and forth over this small edition—Jhon is posing comfortably for the camera, a silent, sweet, and enigmatic young man immersed in his thoughts. His imperturbable gaze and his ways of accepting the photographer’s presence also betray the discreet presence of the photographer in an intense dialogue with his sitter.

Through its subtle sequence of images, the reader becomes complicit in the gentle dialogue between Jhon and Thomas. The pagination makes us participants in this active exercise of attentive observation. By unfolding, a real intimacy is established where affection naturally arises between two people who are looking at each other. Both the book and the images show us what it means to be close to someone. We unfold and peer in with no risk of disturbing this clandestine and captivating connection.

The fanzine’s very limited edition was homemade using an Epson inkjet printer with six colors. The pale cream 120-gram Fedrigoni paper lends the images their subtle color. The choice of paper and the careful printing have resulted in a remarkably tactile book. There is a quality to the images that implies touching by seeing, and feeling the landscapes and bodies by caressing the soft pages.

Only 30 copies were made because Jhon was conceived as a publishing experiment with a high degree of difficulty. Both the small print run and the exploratory nature of the zine make it even more special and precious. Locke Hobbs often travels with one of the copies in his bag to show only to those he feels are sensitive to his work. This is a very important fact, as most of the portraits made of Jhon suggest that the photographer has developed a tender emotional relationship with the subject he portrays. The unfolding of this zine activates within the reader a similar emotional connection, a feat that very few photobooks achieve.

Moises

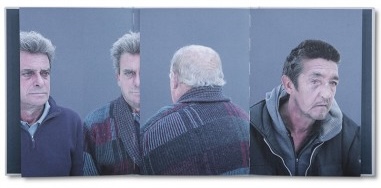

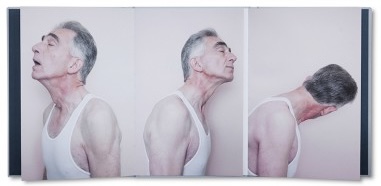

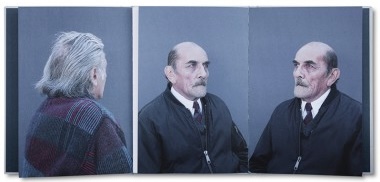

Moisés, by Argentinian photographer Mariela Sancari, is our third and final photobook considered through the framework of our action-verb “to unfold.” The book relays a deeply personal experience lived by Sancari: the attempt to create an impossible image, that of her absent father. This absence dates back to her adolescence, when her father died by suicide. Not having been confronted with his body, she retains for years the fantasy of finding him one day among the crowds. This immaterial image, a product of the imagination, is a driving force for Sancari’s explorations.

How to invoke the presence of what is missing? How to get closer to those we have lost? Sancari decides to take up residence, if only for a while, in Buenos Aires, precisely in the neighborhood of her childhood, a place she has not returned to since her father’s death.

6.8 x 10.2 in (17.5 x 26 cm), 64 pages.

Edition of 1000.Hardcover, offset printing.

ISBN: 9788416248223. © Thomas Locke Hobbs

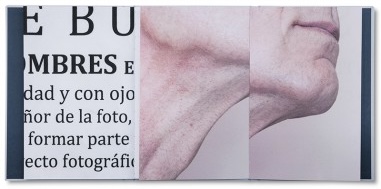

Having lived in Mexico for more than two decades, Sancari obtained a grant from the Centro de la Imagen of Mexico to carry out a documentary project on the absent figure of her father. Her objective is clear from the beginning: to paste posters on the street looking for possible models to portray him. The physical characteristics of those models must be similar to those of her father. A physical portrait and description complete the advertisement.

Sancari works methodically, setting up a studio in the neighborhood’s public square to photograph the models in her father’s clothes. For a few months, she photographs people who are at once strangers and familiar to her. The emotional weight of this photographic gesture is profound. Back in Mexico, the country where she did most of her mourning, Sancari decides to continue her project in order to find a final image for her book. The image, in the end, portrays a single model: a clear memory the artist keeps of her father.

When unfolding the cover, the reader finds two parallel notebooks, with pages on both sides that overlap and intermingle as the reading progresses. They unfold from left to right, then alternate, forming diptychs and triptychs of portraits, giving dimension to the absent father portrayed through men who are roughly the age he was when he died.

The book leads the reader through a labyrinthine process, transposing Sancari’s exploratory experience into the materiality of the object. The structure of the book clearly translates the unsuccessful search.

Near the end of the book, the reader finds a subtle suggestion from Sancari: to return to the beginning by scrolling the pages from the right, a reverse visual journey, retracing the path in the opposite direction. The gesture that readers have already performed in unfolding the book must be performed again, only this time the reader is approaching the task with a new perspective. In the end, the reader returns to the first image in the book, resignifying the circular act—an impossible and potentially endless reconstruction.

Moisés was printed two times. The first edition of 1,000 copies was made in 2015 by La Fábrica, a Spanish publishing house, with an industrial printing method. Despite the large edition size, it sold out after only seven months. The readers understood Moisés. They felt his absence both in the way the portraits were made and in the way they were displayed. A second edition of 500 copies was published in 2022 in the format of a self-published book. For this second edition, the author made small changes in the dedication, the credits, and the final sentence of the book that indicates how to refold the pages. But the unfolding method remained the same. This photobook conceived as a multilayered object is an excellent example of how a Latin American book published in a Spanish editorial industry can have a reach far beyond the Hispanic photobook community and become rare despite its large print run in both editions.

Looking at these books showed us that the poetic act of reading photobooks lies in the phenomenological presence of images that are edited to become haptic, tangible, surprising, and rebel. An encounter with a photobook galvanizes our immediate sensorial perception as readers. Not simply a means to share a story or communicate an idea, a photobook is graphic, printed poetry in paper format, inviting us to perform the act of reading with all senses.