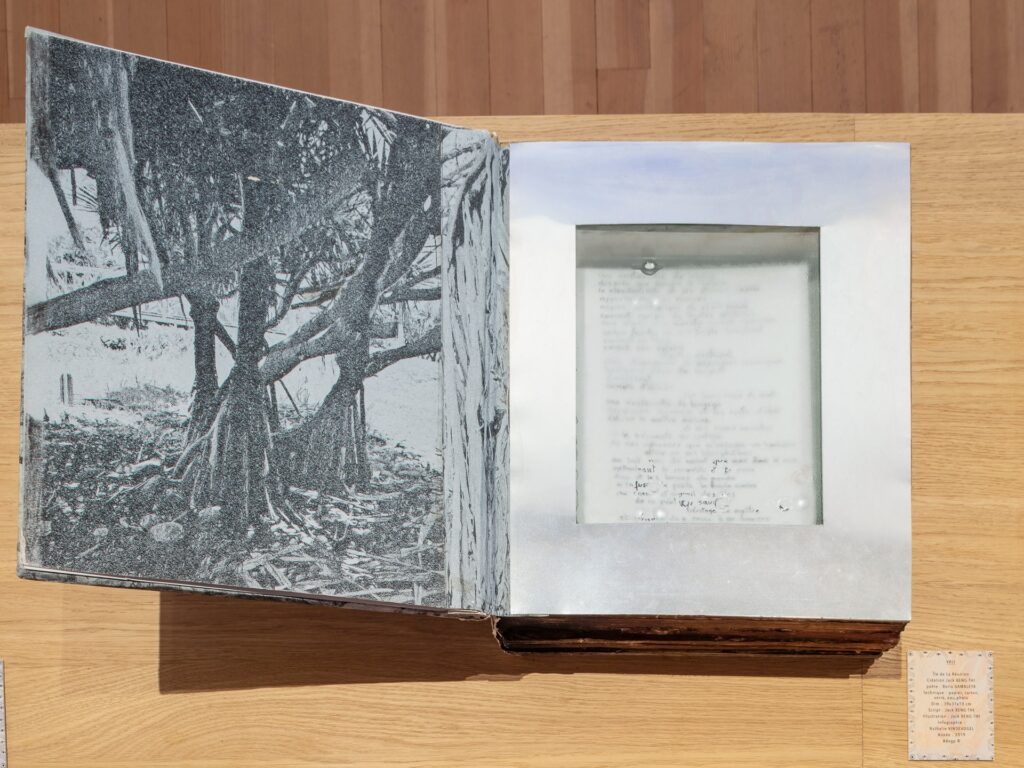

A single sheet of paper rests within a box shallowly filled with water. Presenting as a perfect-bound straight-spine codex, this book is a tight-lidded container of knowledge about the Afrasian Sea. The book’s cardboard covers are not its exteriors per se, but rather, its contents are shrouded by the restlessness of the water within. Condensation clings to the underside of the glass surface, distorting a handwritten poem inside. Save for letters and words occasionally magnified through cohesive water droplets, the book’s illegibility is reminiscent of traditional peekaboo books that shapeshift and befuddle the reader. It could also be shelved alongside the paper-filled pickle jars of From the Literary Kitchen of Tony White (1992), yet instead of bitter vinegar, the words within are buoyed, perhaps by a salty sea brine. Surprisingly, the page of poetry withstands erosion, materially representing what the late poet Boris Gamaleya writes of in Vali pour une reine morte (1973). Personifying the living island of La Réunion as a dead queen, Jack Beng-Thi’s recapitulation of Gamelaya’s poetry in this watery book shores up its irrevocable past, present, and future relationship with bodies: bodies of knowledge, such as books; a particular body of water, the Afrasian Sea; and the mortal bodies of people who know the water.

ADAGP (Society of Authors in the Graphic and Plastic Arts), 2019.

15 x 12 x 4 in (39 x 31 x 10 cm)

Sculpted book using paper, cardboard, glass, water, and photography

Photo: Luca Girardini.

The book’s inside cover image of a natural buttress formed by what appear to be “walking palm” trees exposes how interrelation provides support while blurring boundaries. Beng-Thi renders a “corpoliteracy” by contextualizing the book as the island’s body. The book and the island are each a “platform and medium of learning, a structure or organ that acquires, stores, and disseminates knowledge.”[1] Here, books, bodies, and islands depend on one another even though their definitions are often predicated on singularity. Yet the fluid subjectivity of books, bodies, and islands is precisely what makes them distinct objects of value. For example, it is difficult to know whether an island is coming or going; its pristine isolation often attracts tourists and settlers despite volatility. Bodies also change over time, beyond biological fact; consider those people who are not initially granted the possession of a body equipped with agency or later have such agency revoked, usually through privileged forms of rule and law. And of course, artists’ books themselves, typically rare or specially collected, regularly challenge the boundaries of what can and should be considered a book.

While there is little to no mention of Vali (2019) in writings about Indigo Waves and Other Stories: Re-Navigating the Afrasian Sea and Notions of Diaspora (2023)—an exhibition at Gropius Bau curated by Natasha Ginwala and Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung with Michelangelo Corsaro in Berlin—Beng-Thi’s significant contribution could very well serve as an official catalogue for the show. Set against a map of islands on the wall just behind a long table where the book rests, Vali is accompanied by eight other artists’ books. With the red italicized declaration reading through the center of the map, “Islands of the Indian Ocean are not for sale,” Beng-Thi envisages each book after a respective island (Île de La Réunion, Madagascar, Île Maurice, Îles Comores, and Mozambique). Vali, however, embodies the essence of the entire exhibition by representing a place inhabited by a mixed diaspora of East Africans, Malays, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Indians—people first brought to the island as enslaved and indentured laborers by the French colonial occupation that began in the seventeenth century. Vali’s water evokes the literal sea and offers a metaphor for seeing. Yet these books, like the islands they are named after and the legacy of those who cultivated them, are not for patrons to touch, let alone purchase. Only trained docents wearing gloves can turn the pages, and even they are unable to tamper with the single wet folio of Vali, a brilliant encapsulation of meaning, materiality, and critique.

Most of the human body, like the Earth, and arguably Vali, is constituted of water. As human bodies mature, they dry, progressing from 75 percent water as infants to 55 percent as seniors. Like their respective islands, these books merge out of an incomprehensible gulf of innocence into discrete statures of lonely objecthood. Beng-Thi’s concern for the islands of the Afrasian Sea surfaces through attention to both the physical body and social bodies implicated in historic island life. Drowned literally by rising sea levels fueled by imperialist exploitations and capitalist extractions as well as dampened and damned by processes of colonization and enslavement, the poem substitutes a dead queen’s body in place of the island and its inhabitants. Similar to the water droplets in Vali, and Vali itself among its sibling texts, an object’s subjectivity coheres through the hold of individuation. In other words, the book becomes the dead queen through its liquid opacity. While words in conventional codices act as grains of sand accumulating into a seemingly solid body or landmass of knowledge, in the case of Vali, words demonstrate unfixed meaning. With an ocean continually lapping at the shore’s edge, counter to the hegemonic Western rhetoric of progress, Beng-Thi resurrects Gamelaya’s dead queen—the island of La Réunion—through subsuming Gamelaya’s poem in water. In Vali, revival is necessarily rooted in the inevitability of submergence. As Ndikung explains, “it is not just the content that matters, but also finding the right container for the right content.” Obscuring as it condenses, Vali’s water shifts focus from the poem to the book as a whole, through which the privacy and honor of the island is reinstated.

The incorporation of water as an unexpected site for opacity resists the liquidation of the book. It is not mass-produced and is possibly unfit for stores and library shelves—after all, Vali could very well pose a threat to its neighboring texts, and its shelf life is intentionally unknowable. Referencing the valiha, an instrument sometimes used to summon spirits, Vali is a transaesthetic song not derived from the white paper within, but out of the Blackness of the book’s water, evocative of the Afrasian Sea. Responding to Pierre Bélanger and Jennifer Sigler’s cry to “let wet matter,” Beng-Thi’s artists’ book dissolves the boundaries between book, body, land, and sea while revealing the tensions held between conceptualizations of book art, island borders, and Black subjectivity. According to Jenna Sutela, “we are as dependent on water as we are on the technologies that seal us from it.” In that case, do not touch, attempt to collect, or even think of buying Vali. Black and Asian bodies, like the Afrasian islands and the materials used in making this book, while boundless, are off-limits and, most importantly, not for sale.

- (1)

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Pidginization as Curatorial Method: Messing with Languages and Praxes of Curating (London: Sternberg Press, 2023), p. 44.

ADAGP (Society of Authors in the Graphic and Plastic Arts), 2019.

15 x 12 x 4 in (39 x 31 x 10 cm)

Sculpted book using paper, cardboard, glass, water, and photography

Photo: Luca Girardini.