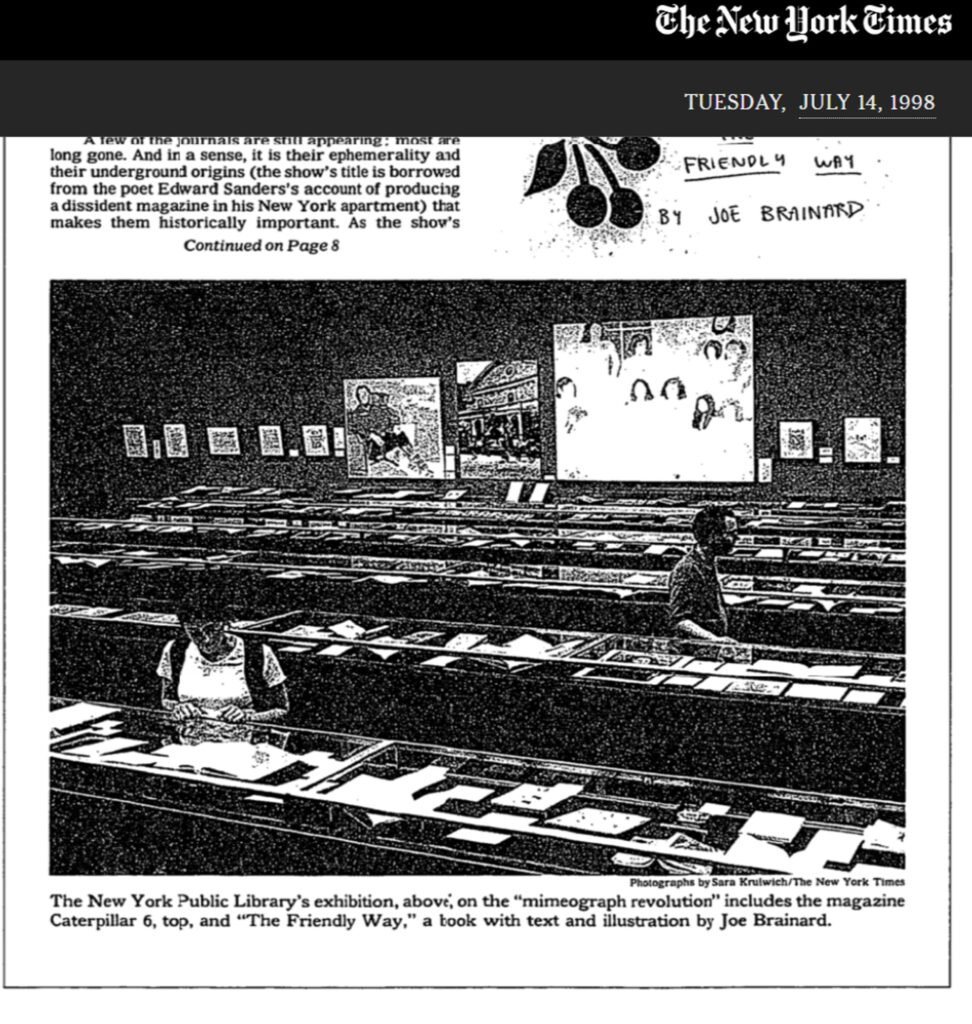

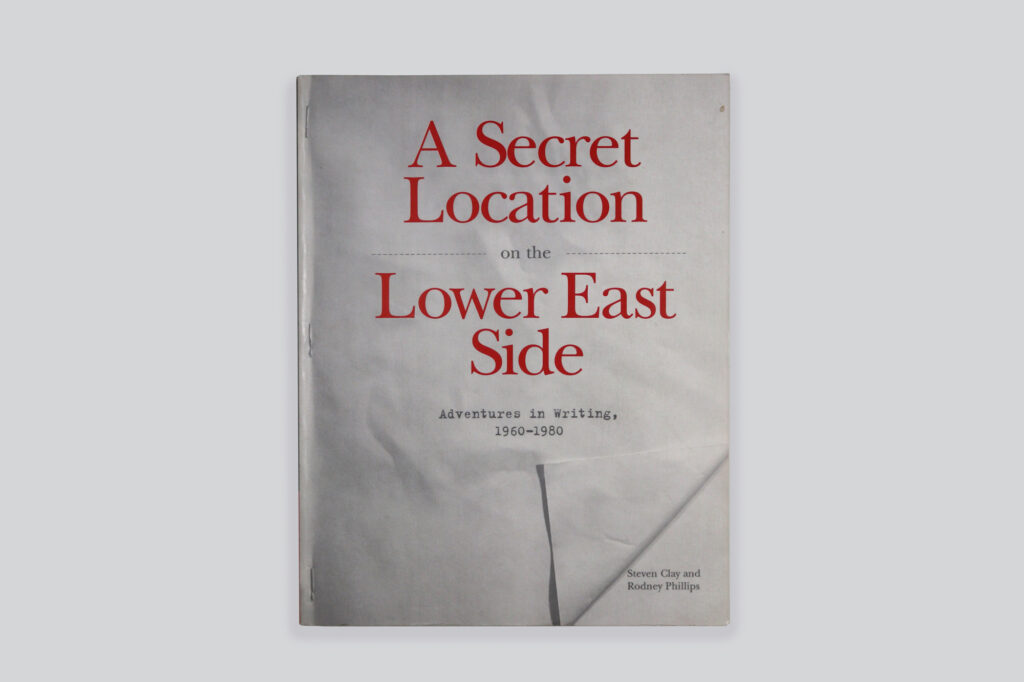

In 1998, the year of Dick Higgins’s death, the New York Public Library opened an exhibit titled A Secret Location on the Lower East Side, which celebrated and historicized the mimeo revolution and small press movement of the years between 1960 and 1980.[1]In his preface to the catalogue, Jerome Rothenberg suggests that the marginal presses of the type included in that show were the bearers of the mainstream of American poetry, and that “the part by which [American poetry] has & will be known” is “the creation of those poets who have seized or often have invented their own means of production and of distribution.”[2] Thus, Rothenberg, amplifying the vitrines’ rarities, positioned the value of the small press in its marginality and, more precisely, in what poet/scholar Michael Davidson has called its revival of aura through the utilization of “cheap, portable print technologies to render ‘authentic’ gesture.”[3]

The history of the Something Else Press—which was included in the NYPL show and its catalogue—is inextricable from the context of the “mimeo revolution” as presented by this exhibit. However, SEP ran counter to some of the “revolution’s” most salient rhetorical and production strategies in a few important ways, some more obvious than others.

For starters, SEP’s insistence on quality materials and bindings is conspicuously out of place among the stapled, poorly reproduced, “low-end”[4] exponents of mimeo revolution publishing.[5] Stapled chapbooks and magazines, often in very small print runs with mimeo-printed letter-size sheets, poured out from corner printshops, printing co-ops, and the basement of St. Marks Church, and were often assembled by friends of this or that publisher. Hettie Jones’s description of the making of Yugen in the early 1960s is illustrative of the way such practices signified outsider “authenticity”: “When we got the early issues they were just in pages, so we had parties—stapling parties. [. . .] They would pass pages to one another and then somebody did the stapling on the spine. [. . . ] And we got drunker as the night went along. But it’s amazing, those little magazines—they survived!”[6]

CBA collection no. REF.BC.1044

Davidson has described the fast and cheap production practices of mimeo-revolution publishing as “part of an expressive poetics that validated personal gestures of discovery and speculation over artisanal values of order and control.”[7] While Charles Olson would marvel at the speed with which his work was printed straightaway (via mimeo) in The Floating Bear,[8] Higgins was hardly interested in the “speed and efficiency”[9] of inexpensive means of reproduction, nor in cheap and portable printing methods like mimeo. On the contrary, Higgins was extremely careful and concertedly purposeful about SEP’s design[10] and proud of his printing know-how attained in a commercial pre-press production department. He prefaced the catalogue of SEP’s 1965–66 publications with an in-depth essay titled “What to Look for in a Book—Physically,” in which he lays out his standards for a well-made book and defines SEP production values to justify its higher retail prices.

CBA collection no. FA.B125.2520

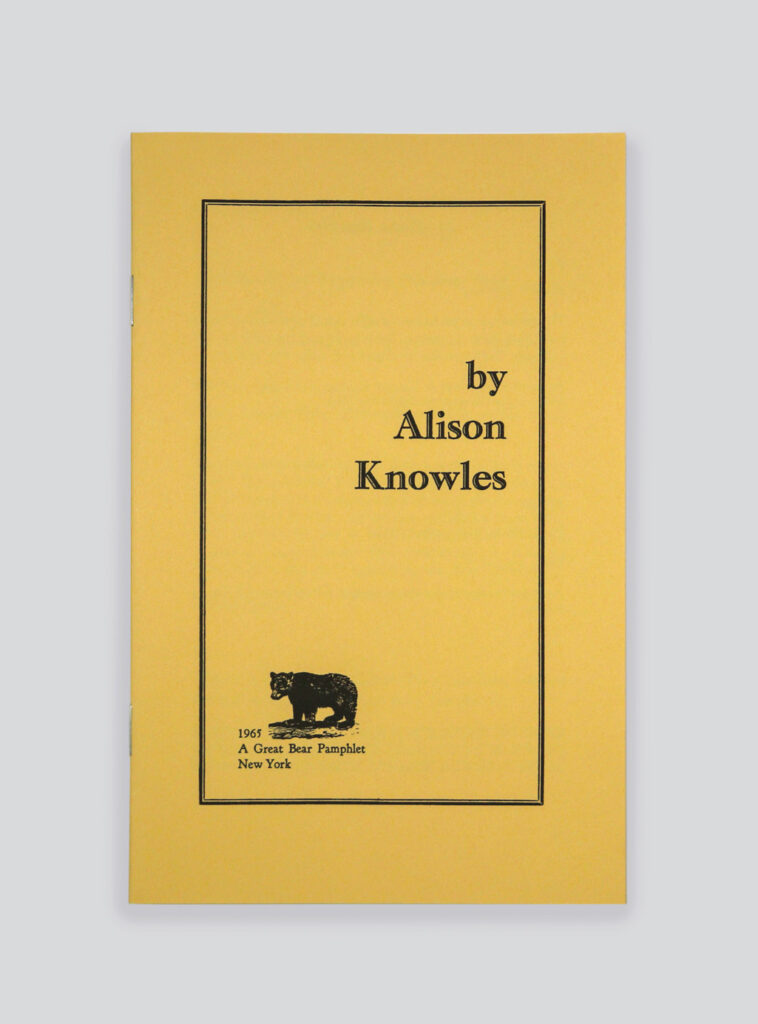

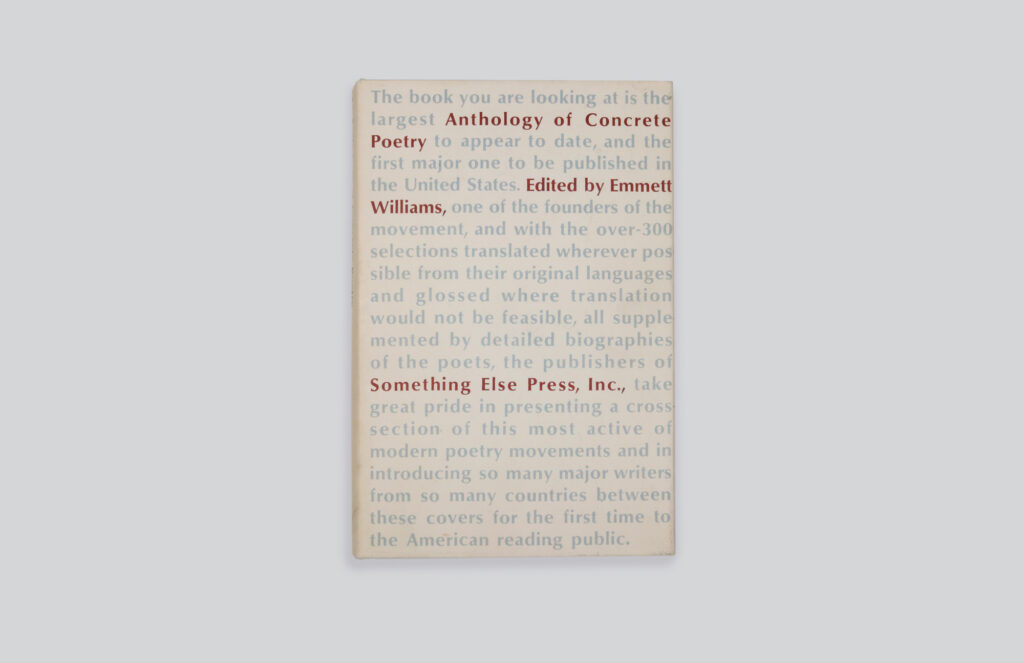

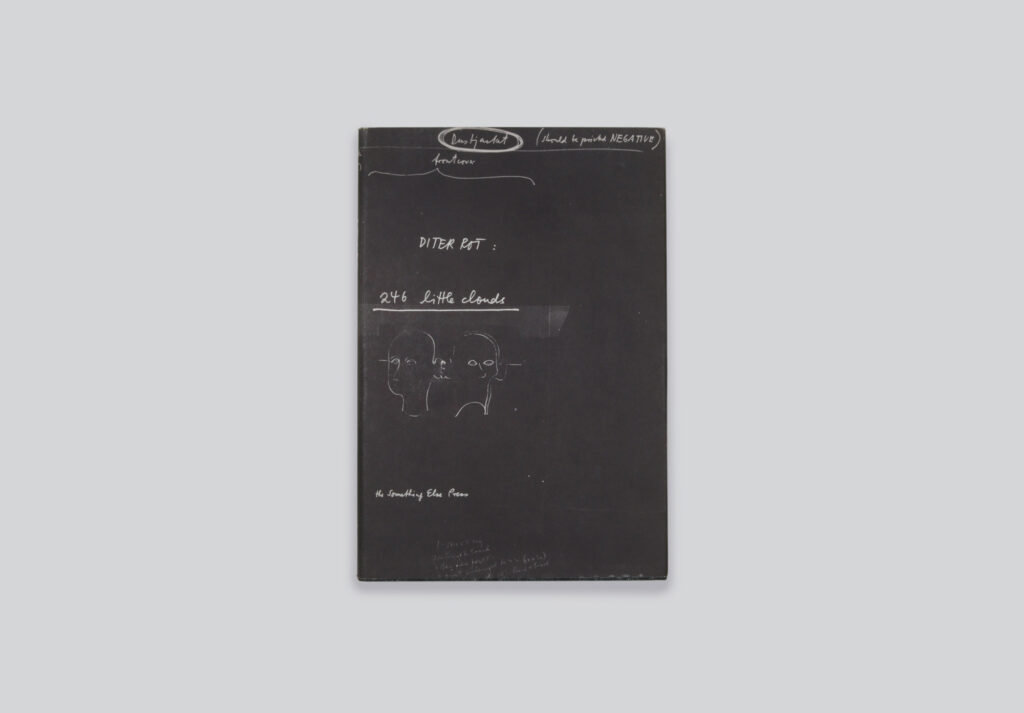

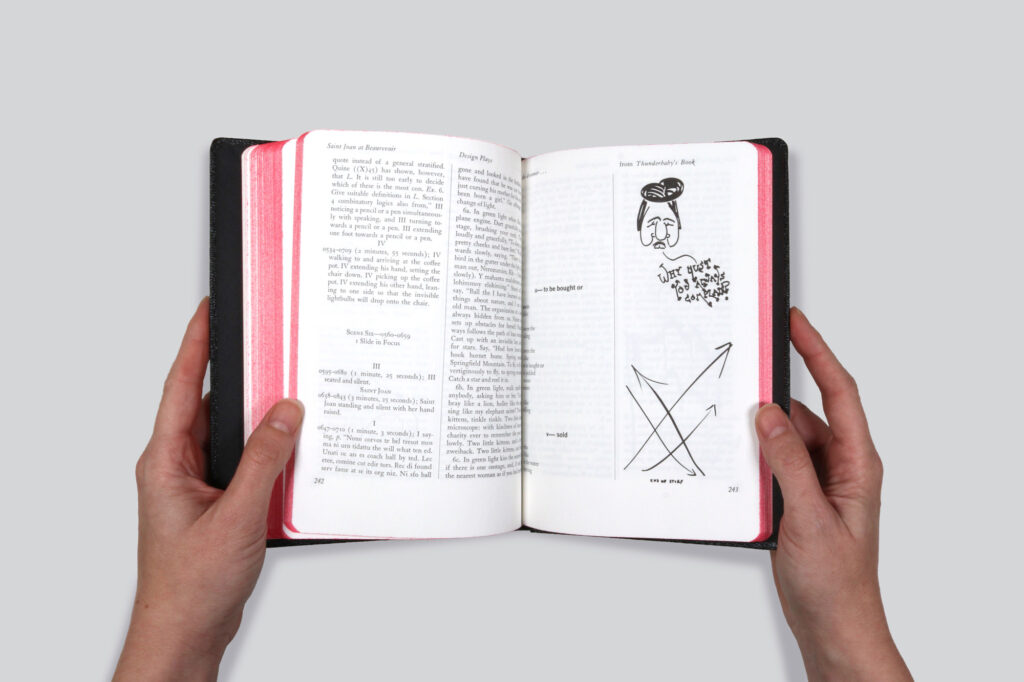

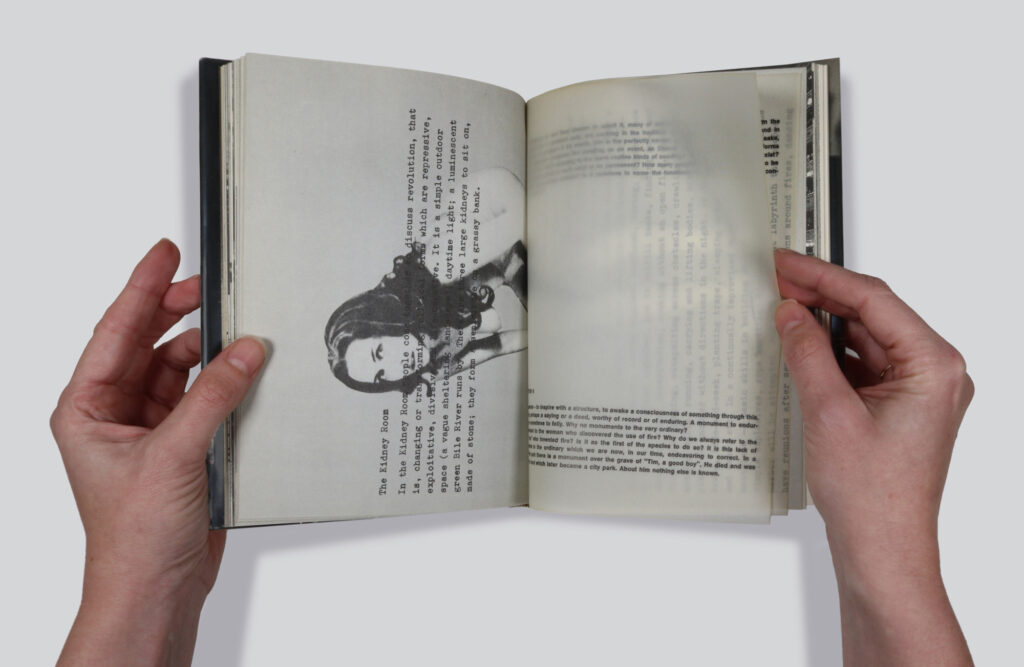

Only SEP’s Great Bear Pamphlet series, designed to be sold in supermarkets, was saddle-stitched. For the most part, SEP’s titles appeared in hardcover editions: cloth over board with dust jackets. These included Ray Johnson’s The Paper Snake (1965; SEP’s second book), Claes Oldenburg’s Store Days (1967), Merce Cunningham’s Changes: Notes on Choreography (1968), Daniel Spoerri’s An Anecdoted Topography of Chance (1966), Diter Rot’s 246 Little Clouds (1968), An Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967), John Cage’s Notations (1969), Gertrude Stein’s Geography and Plays (1968) and Lucy Church Amiably (1969), and many others, all with acid-free paper and durable sewn bindings, some with glassine jackets and additional specialty work like inserts or translucent sheets (cf. Fantastic Architecture, 1970). The lush bible-style edition of Higgins’s own Foew&ombwhnw (1969)—which included the seminal essay that coined the term Intermedia—boasted rounded corners, foil-stamping, and red edge-painting.

Unlike many of the heroes of Rothenberg’s “poet-publishers” narrative, Higgins would not claim authenticity for his publishing endeavor by juxtaposing “low-end” production and design against perfectionist artisanal printing associated with high-end private press (hand-press printing, hand-set type, acid-free papers, fancy leather bindings), which asserted a more conservative politics of craft-oriented aesthetics. He stood in neither camp. His resistance to the “low-end” is not snobbery, nor is his insistence on paper quality, etc., akin to the “order and control” associated with “fine” or “private” press works. Rather, both have to do with his being “adamantly opposed to our [Fluxus artists] potential marginalization for the sake of ideological purity, [because] we were already marginalized enough in the cultural world without adding to the problem.”[11] This position, in fact, led to a temporary split with Fluxus guru George Maciunas.

Higgins’s critique of Maciunas’s publishing work (the making of Fluxus editions) speaks to a complicated relation to the mimeo-revolution values put forward by the Secret Location show. “Maciunas’s way of publishing stressed the original design, the unusual materials, and the handmade,”[12] notions that would ring true for many of the Secret Location publishers. Though Higgins was an innovative designer, and was of course interested in unusual materials to a point, he was not so taken with the “handmade,” nor its attendant invocation of authenticity. Mainly, his beef with the handmade had to do with its hindering the wider reach of the content. When Higgins referred to the Fluxus editions not as books but as “prototypes,” he was lamenting the fact that the process was never meaningfully industrialized, and the resulting editions were not widely available. “Our [Fluxus] productions were ‘collectibles,’ and perhaps we were simply producing as much ‘for the collector’ as traditional artists.”[13] (SEP did publish several special editions and Fluxus-style boxed works to raise money for the press, but this kind of collector’s edition was a very small percentage of their catalogue.) In essence, Higgins’s critique casts Maciunas as an inheritor and propagator of the livre d'artiste tradition, in that these were really collectible editions, even if different in aesthetics and sale price from their European antecedents and contemporary counterparts.

Due to a self-acknowledged “strong populist streak,” Higgins was wary of the “Fluxboxes and publications [as] too elitist.”[14] This concern extended to the coterie tendency of the New York small presses he saw around him. Higgins even found their editorial choices either passé (“the best poems of the 1950s are being written today by John Ashbery and Co.”[15]) or too focused on what he deemed established traditions (Beat and Black Mountain), which he termed the “Going Thing” School, and which “converged into the St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery style of the 1960s.”[16] His modernist cosmopolitism—and his knowledge of an international avant-garde—perhaps got in the way of wholeheartedly embracing “local” scenes like the one on New York’s Lower East Side.

Of course, SEP does share with contemporaneous mimeo mag and chapbook publishers an aversion to the commercial tycoon publishers and their editors, there is a nuanced difference even on this point. SEP’s origin story is inextricably linked with the idea of an alternative to trade publishing. Allison Knowles’s off-handed response to the idea of Shirtsleeves Press—”Why don't you call it something else?—prompted Higgins to take her words literally: “I liked the implication that whatever the commercial publishers chose to publish, we would always publish something else.”[17] Thus, SEP began as a counteraction to commercial publishing, akin to the thermodynamic law of equal and opposite reaction, quite different from the gesture of disavowal of—and disengagement from—commercial publishing typical of counterculture small presses.

Higgins kept an eye on commercial publishing in order to further his own cause. He was adamant that SEP operate “through the ‘book trade’ format rather than that of small presses as such,” by which he may have meant the mimeo-oriented, low-circulation small presses of the early 1960s. Instead of a “secret location” on the Lower East Side, he chose an office at 160 Fifth Avenue in the publishing district near the Flatiron Building. The business card he printed for his first editorial director, Barbara Moore, sported a company catchphrase below the press name: “America’s Quality Avant-Garde Publisher.” This tagline affirmed Higgins’s obsession with quality book production while at the same time distancing SEP from the counterculture exemplified by Ed Sanders’s credo for Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts (1962–1965): “I'll print anything.”

SEP’s office, business cards, and motto, ringing with Fluxus-like absurdism, poked fun at commercial, mainstream “American” publishing, while antagonizing the counterculture’s anything-goes gesture. At the same time, these choices amplified the earnest strivings of SEP: “Whatever we did, it would have to follow with our name, to be ‘something else’ from what the commercial publishers were doing.”[18] So, too, SEP’s high production values went hand in hand with the mission of finding “the largest possible public” for the new intermedia arts. Higgins embraced the hardcover-plus-paperback model for many of SEP’s titles, though some were paperback-only. SEP’s print runs generally numbered in the one thousand to four thousand range—lower than the print runs of commercial publishers, but much higher than the print runs of other publishers included in the Secret Location show (hovering between fifty and five hundred) and those of most small press books even today.[19] Higgins took the role of publisher rather seriously, even if his self-proclamation as “president” of SEP carried a note of irony.

Nonetheless, in an essay titled “Some Things Else About Something Else,” published in the takeaway brochure of a 1991 exhibition, Barbara Moore writes that she was “baffled by the conformism” of Higgins’s choice of format—the well-made clothbound book—as a vehicle for avant-garde ideas. No doubt others in the Fluxus and Happenings orbit perceived Higgins’s allegiance to the “old” form of the book as conservative or “conformist.” Moore writes, “Dick was committed to the most radical art concept of the time, intermedia [. . .] yet he wouldn't tamper with the formalism of the book.” She came to the conclusion that SEP books were “wolves in sheeps’ [sic] clothing” that “infiltrated the establishment, laying the groundwork for the artists'-book revolution to come.”[20] Earlier, Moore, along with Jon Hendricks, made a similar argument, “Esoteric books could also be made to look mass-produced, as with most of the publications of the Something Else Press [. . .] so that standard libraries would be more willing to put them on their shelves.”[21] Yet, SEP publications didn't just “look mass-produced,” they, in fact, were, and for good reason.[22] Moore’s argument says more about the way the art world and artists’ book context had (and has) trouble assimilating SEP’s project to claim nonmarginal, non-esoteric status for the content and artists it published.

The catalogue for A Secret Location echoes Moore’s idea in describing the “radical achievement” of SEP books to “slip avant-garde content into what looked like ‘regular books’ and then to get those books into bookstores and libraries around the world.”[23] The entry for SEP in A Secret Location also implies the press’s dissimulation (or sneaky subversion) when it describes Higgins’s Foew&ombwhnw[24] being “disguised as a prayer book.”[25] Yet, the blackletter fonts and other “medieval“ flourishes in SEP books, and the prayer-book binding of Foew&ombwhnw in particular, are obvious nods (just a tad reminiscent of William Morris’s medieval predilections) to pre-Renaissance culture and the integrated curriculums of early modern scholastic traditions (where math, music, poetry, and rhetoric were equal in the quest for knowledge without the “compartmental approach” of modern departmental separation), which Higgins held in high esteem as precursors of intermedia thinking. Higgins’s interest in what Moore calls the “conformism” and “formalism” of the book was an engagement with precisely the technology of printed and bound adjacent pages that had spread gospels, new beliefs, science, and aesthetics since Guttenberg’s bible through Luther, Erasmus, Sterne, etc. And, while Edition Hansjörg Mayer and other European art publishers followed fairly conventional livre d'artiste traditions of a commerce based in selling the work of artists in deluxe codex form, Higgins published literature and ideas (as much, if not more than “art”) in durable trade editions and was rarely engaged in making collectibles.

With a background in theater and music furthered by studies with Henry Cowell and in John Cage’s New School course (where George Brecht’s idea of event notation took hold), Higgins took interest in the repeatable function of performance scores of all kinds—what he would later term “exemplativist” art.[26] The book offered a similar space of repeatability, one that could have a life (like Happenings and Events) outside of traditional art institutions because of its more democratic form of circulation,[27] and as an object to be returned to, experienced differently each time. “We are not interested in built-in obsolescence,” he wrote, contrasting SEP books with those of commercial presses, whose “mass market” paperbacks with their quickly brittle and yellowed acidic pages were by that time ubiquitous. “We want our books to be as fresh ten years from now as they are today, and as much of a joy to behold.”[28]

To be returned to, the book had to be durable in form as well as content, hence Higgins’s extensive deployment of the hardcover form. He relied on its substantialness and its familiarity, its ability to hold its own in the bookstore, in the library, or on the personal bookshelf, and to incontrovertibly, self-consciously connote “book,” to be as book-like as possible—a book like any other, but better.

No doubt, Higgins understood the book as the primary authority in his cultural moment[29], seeing it as an instrument to historicize the aesthetic movements and art-innovations of Fluxus and related scenes. Indeed, SEP’s list represents a good part of what we understand as the history of the postwar avant-garde and its lineage[30]; the publisher’s catalogue was a purposeful strategy. It provided a context in which Fluxus and its friends could be read and understood, to become “points of reference”[31]:

Higgins strategized the charting of intermedia lineages: SEP put six books by Gertrude Stein back into print (“to steal her back from the rarebook [sic] freaks and collectors”[32]), repositioning her as a central predecessor for the new art, much the way Surrealism claimed Comte de Lautréamont as its forebear; republished a nineteenth-century book on games to imply historical precedent for Fluxus “art-amusements”; revived a 1950s essay by Marshall McLuhan on sensory experience in aesthetic appreciation; and, in response to facile criticisms of Fluxus as Dada, SEP republished the Dada Almanach, to “show that we weren't by showing what dada was.”[33] In pursuit of these revisionist historical goals, SEP’s ambitious print runs ensured that the books would—eventually—circulate, even if distribution systems created obstacles to getting them into readers' hands right away. If they had to be remaindered or given away, that would still be circulation. Moreover, SEP’s print runs announced their intention to circulate, a performative marker of the seriousness of the endeavor and the historical importance of the content. This was not, as Moore and others intimate, a frivolity: higher print runs were necessary to back up the claim that SEP was bringing you, as a 1970 SEP catalogue boasted, “Tomorrow’s Avant Garde Today.” At the same time, SEP’s books laid out “exemplative” potentials for new forms of interstitial intermedia such as the “artists book,” which had only begun to attain self-conscious awareness as an artistic practice and as a specific genre of book in the year leading up to SEP’s closure.[34]

Thus, the book was not a “formalism” for Higgins, it was form—the form he needed and trusted to get ideas across, to bring “the work [of Fluxus and intermedial artists] to the largest possible public in an undiluted form.”[35] He used the book not to “infiltrate the establishment” but to establish a space for himself and his allies, to create a context and system of valuation for their work. The book, specifically the high-quality “mass-produced” book, was necessary to circulate authoritative arguments for the beliefs of intermedia, to assign value—through presence—to what might otherwise remain marginal. Higgins’s publishing politics and practices diametrically opposed the production values—the reification of “speed and efficiency”—promulgated by the mimeo-revolution publishing boom of his time, perceiving its “authentic gesture” as a path toward self-marginalization. Though Higgins did not “invent” his “own means of production,” preferring traditional book forms, he experimented with alternative distribution systems for SEP and participated influentially in collective distribution and advocacy efforts in the small press community of the late 1960s and 1970s.[36] With the “traditional” book as his media, Higgins used his capital, know-how, connections, and (rather self-conscious) privilege to assert an autonomous arbitration of aesthetic value, independent of commercial and institutional frameworks. Despite the press’s financial failures, SEP’s books have proven to be, in Higgins’s words “more durable than the legend. Their ideas last.”[37]

- (1)

For more on the impact of this exhibit, see my essay “‘Power to the People’s Mimeo Machines!’ or the Politicization of Small Press Aesthetics,” Harriet (blog), February 3, 2020, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/2020/02/power-to-the-peoples-mimeo-machines-or-the-politicization-of-small-press-aesthetics.

- (2)

Jerome Rothenberg, “Pre-Face,” A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980, eds. Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips (New York Public Library: Granary Books, 1998) p. 9.

- (3)

Michael Davidson, Ghostlier Demarcations: Modern Poetry and the Material Word (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997) p. 31.

- (4)

A term used by Charles Bernstein in a 1994 talk on “The Economics of the Small Press: Poetry Publishing,” printed in Talking the Boundless Book: Art, Language, and the Book Arts, ed. Charles Alexander (Minneapolis: Minnesota Center for Book Arts, 1995).

- (5)

“The mimeo in ‘the mimeo revolution’ is more a metaphor for inexpensive means of reproduction than a commitment to any one technology,” as can be seen from the numbers: “In 1965, 23% of literary presses were mimeo, 31% offset, 46% letterpress. [. . .] By 1973, offset had jumped to 69%, with letterpress at 18%, and mimeo only 13%.” Charles Bernstein, paraphrasing Loss Pequeño Glazier, in Talking the Boundless Book, p. 38.

- (6)

Hettie Jones, “An Interview with Hettie Jones,” by Stephanie Anderson. Chicago Review 59, no. 1/2 (Fall 2014/Winter 2015) pp. 79-90.

- (7)

Davidson, Ghostlier Demarcations, p. 31.

- (8)

Floating Bear was a magazine edited by Diane di Prima and LeRoi Jones.

- (9)

Davidson, Ghostlier Demarcations, p. 31.

- (10)

See especially Higgins’s notes on page layout and type choices in “Two Sides of a Coin: Fluxus and the Something Else Press,” Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, eds. Steve Clay and Ken Friedman (New York: Siglio 2018) p. 145.

- (11)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 144.

- (12)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 142.

- (13)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 143.

- (14)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 143.

- (15)

“Postscript to Postface,” Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 85.

- (16)

“Postscript to Postface,” p. 85.

- (17)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 151.

- (18)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 145.

- (19)

For a discussion of the financial difficulties brought on by SEP’s substantial print runs, see my essay “Dick Higgins, Publisher: Notes Toward a Reassessment of the Something Else Press Within a Small Press History” in The Improbable 1 (New York: Siglio Press, Fall 2020).

- (20)

Barbara Moore, “Some Things Else About Something Else,” folding brochure for the exhibition Something Else Press at Granary Books, New York, September 5–October 5, 1991.

- (21)

Jon Hendricks and Barbara Moore, “The Page as Alternative Space: 1950 to 1969,” in Flue exhibition catalogue, (New York: Franklin Furnace, December 1980) reprinted in Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, ed. Joan Lyons, (Rochester: Visual Studies Workshop, 1985) p. 92.

- (22)

Steve Clay’s “A Something Else Press Checklist” (in Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, pp. 176–235) shows the print runs of SEP books mostly exceeding one thousand copies. Merce Cunningham’s Changes: Notes on Choreography (1967) came out in cloth (hardcover) only, with 3,761 copies. Many of SEP’s hardcover books had additional paperback editions: 1,530 copies of Stein’s Geography and Plays (1968) were bound with cloth over board, and 1,732 copies in paper wrappers.

- (23)

A Secret Location on the Lower East Side, p. 33.

- (24)

Dick Higgins, Foew&ombwhnw: A Grammar of the Mind and a Phenomenology of Love and a Science of the Arts as Seen by a Stalker of the Wild Mushroom (New York: Something Else Press, 1969).

- (25)

My emphasis. See A Secret Location on the Lower East Side, p. 137.

- (26)

See Dick Higgins, “An Exemplativist Manifesto” (Unpublished Editions, 1976), reprinted in Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, pp. 247–255.

- (27)

See Higgins’s thoughts on the dangers of an “elitism” in Fluxus editions, in “Two Sides of a Coin: Fluxus and the Something Else Press,” Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 143.

- (28)

Dick Higgins, “What to Look for in a Book—Physically,” (1965) in Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, 128.)

- (29)

Lucy Lippard notes that in the 1960s and 1970s, despite advances in computer technologies of information storage and retrieval, “the book remain[ed] the cheapest, most accessible means of conveying ideas.” See Lucy Lippard, “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” in Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, p. 45; originally published in Art in America 65, no. 1 (January–February, 1977).

- (30)

Allan Kaprow, John Cage, Claes Oldenburg, Ray Johnson, Bern Porter, Merce Cunningham, John Giorno, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Dieter Roth, George Brecht, Jackson Mac Low, and Brion Gysin were among SEP’s contemporary authors, and its list included avant-garde forbears Luigi Russolo (Italian Futurist composer), Gertrude Stein, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Marcel Duchamp.

- (31)

“Postscript to Postface,” Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 87.

- (32)

“Postscript to Postface,” Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 86.

- (33)

“Postscript to Postface,” p. 86. Cf. Higgins’s later publication of his research on “Pattern Poetry” is a similar intervention—contextualizing modernist visual poetry (Apollinaire’s calligrammes, Lettrisme) and Concrete Poetry within historical precedents.

- (34)

For a discussion of the beginning of a critical discourse on “artists books” see Stefan Klima, Artists Books: A Critical Survey of the Literature (New York: Granary Books, 1998) pp. 7–20. Klima suggests that no critical discourse on this field of artistic practice existed, at least under that name, in print until early 1974, although there had been a handful of museum exhibitions focused on “Artists Books” in the early 1970s, of which only the 1973 Moore College show used that term. That show and its catalogue have the distinction of using the term for the first time.

- (35)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 145.

- (36)

See more on SEP’s distribution strategies and Higgins’s work with COSMEP (Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publishers) in my essay “Dick Higgins, Publisher: Notes Toward a Reassessment of the Something Else Press Within a Small Press History” in The Improbable 1, 2020.

- (37)

Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press, p. 167.