Let’s talk about money and publishing artists’ books.

Secret Riso Club (Tara Ridgedell): Learning to become more comfortable with having conversations about money is really important. As artists and creatives who would say they reject capitalism, it can be uncomfortable to have those conversations, but the more comfortable you are with it, the less taboo it feels to discuss, and the more transparency you're able to offer. But it takes time to learn. It's so helpful to know people who are willing to have those conversations and share resources and that kind of knowledge. We're really grateful for that and hope to contribute to that, as well.

Gnomic Book (Jason Koxvold): I didn’t necessarily intend to make books; I stumbled into it mostly from how much pleasure and fulfillment I took from making my own book. It's a great conversation to be having, and the more we talk about this stuff, the more misconceptions we can avoid.

How does community play a role in your creative economy?

Secret Riso Club (Gonzalo Guerrero): We do a lot of workshops, print our own work, offer printing for other artists. . . . It's a hybrid that's similar to a design studio. The community aspect is very important to us, which means trying to open the studio to others. We’re creating community around a very necessary kind of mutating process from a design studio, to a publisher, to a creative studio. It's hard to put a label on it like “publisher,” because other projects specifically have a financial model around that, and what we’re doing is more open.

Flying Fish Press (Julie Chen): I could not do this on my own without help from the people who are making my paper, making my film and plates, and helping me in the bindery. It would be hard for anybody to do all parts of the process on their own. I'm not saying that there aren't people out there who are total one-person operations, but art often involves more than one pair of hands, and I really want to always acknowledge that.

I've been teaching for a long time, and sometimes students who come into book art without knowing that much about it are kind of shocked if you don't make all the books yourself. I tell them I would never sleep if I had to do every single book process. Then they ask, “How is it your work?” And it opens up a productive conversation about the role of the artist, the craftsperson, the studio assistant, and people start to understand more about what goes into this. This is just reality, and we shouldn't be ashamed about saying, “I need help.” Even though I depend on other people to help me do this, it's still my vision, and it still has to be made to my standard.

What is the framework for thinking about how finance interacts with the different types of projects you do? Do you have a model in which you're budgeting and/or projecting income from projects?

Secret Riso Club (TR): For our collaborations, we have a breakdown of four different agreement options. One is that Secret Riso Club takes on all the costs, gives the artists a stipend, and keeps all the proceeds from the book—that's one extreme. The other extreme is the artist pays for everything, and then we purchase books from the artist at cost in order to sell on our end. There are two other options that are more in-between. Our previous agreement was a kind of split, being 50/50 for the artist, but we also realized that it didn’t take into account all the design work and material costs. There wasn't quite enough on our end being covered, and honestly, that doesn’t work for every artist, either. We wanted to give people a chance to be able to make something and be well compensated, and for our costs to be covered, as well.

Secret Riso Club (GG): I also want to mention that our income comes from different sources. I do mostly graphic design, and we do commercial printing and classes that allow us to invest in new machines and new books. In the past two years, Secret Riso Club has been growing. The majority of money that is made goes back into the studio, aside from basic living costs.

Gnomic Book: Our funding model has always been fairly straightforward. It's something we have occasionally not been super comfortable with, but originally it was that the artists would bring the cost of production, plus a small percentage to cover design, and then they would receive an agreed-upon number of books—usually in the realm of one hundred—that they can sell themselves. The only thing we ask is that they don't sell them in direct competition to Gnomic.

Some artists felt like that was fair and generous, and some artists felt like we should be doing more profit sharing. The new model is: If an artist brings one hundred percent of the funds, then they receive fifty percent of the profits on books sold through direct channels. If they bring none of the funds, then they receive none of the profits. So it's a sliding scale. There are other factors, such as running a presale, or in the case of a few of our books, the artists have received grants, or one artist had a few wealthy benefactors who agreed to fund the production of the book alongside the presale. Presale requires a lot of work organizing, generating assets, and doing press outreach, sometimes setting up a Kickstarter, or building the functionality on our website to host it. But we're not on the grand scale of photobooks. Some photobook presses ask an artist to bring fifty thousand dollars or eighty thousand dollars; typically, our scale is smaller, where the cost of making a book with us is between six thousand and twenty-five thousand for an independent artist, and then, if we're doing corporate, then we would charge more.

Flying Fish Press: I started Flying Fish Press in the mid-eighties on a shoestring budget, publishing books with very little money, and slowly built up a capital account that helps pay for future projects. It’s important for me to acknowledge that the first five to seven years of the press, I didn't have to make any money because I had support from a partner. I was able to take the money that I was making from selling books and throw the entire amount back into the business for at least five years. I know that's unrealistic for a lot of people who don't have that kind of support to start with. However, I feel it's important for me to own that, and to say I feel really fortunate and grateful that I had that kind of access. I ended up getting divorced, but by that time the press was able to start paying for itself and pay me a modest salary, only because I had that strong beginning that I was able to really build on.

Almost since the beginning, I've had a studio assistant helping me, and that has been one of the big pieces of overhead. When the press had to start paying me, I just had to insert that big chunk of income into the equation. From the beginning, I've really been mindful of how to think about the budgeting process for a project and estimating the assembly, because I don't know exactly how long it's going to take to put together. I’ve made some mistakes over the years, but I've gotten better at estimating more accurately how many person-hours are going to go into making a copy of a book.

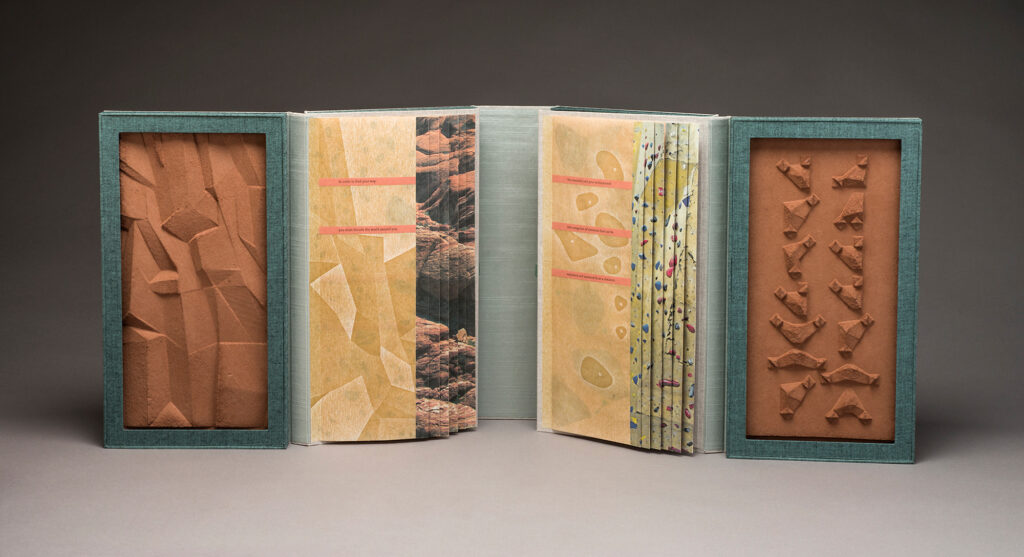

When a project is first starting out, I'm not thinking about the budget at all because if I start thinking about budget constraints immediately, it’s going to hamper the creative process. I will allow myself free rein in the beginning, telling myself: Don't worry about how much it's going to cost; figure out how the object needs to be in order for it to do the thing you need to do. But once I get serious about the project, I need to start looking at what the options are, and ask questions such as: Should we get all the paper made? Who's going to make it? How much is it going to cost? Once the initial envisioning of the project is underway, then the financial reality of the situation does play a role.

How do you decide where exactly you're going to put funds on a particular project? I know that a lot of times, publishers have to make those difficult decisions between putting more money into an aesthetic decision versus an edition size, and so on.

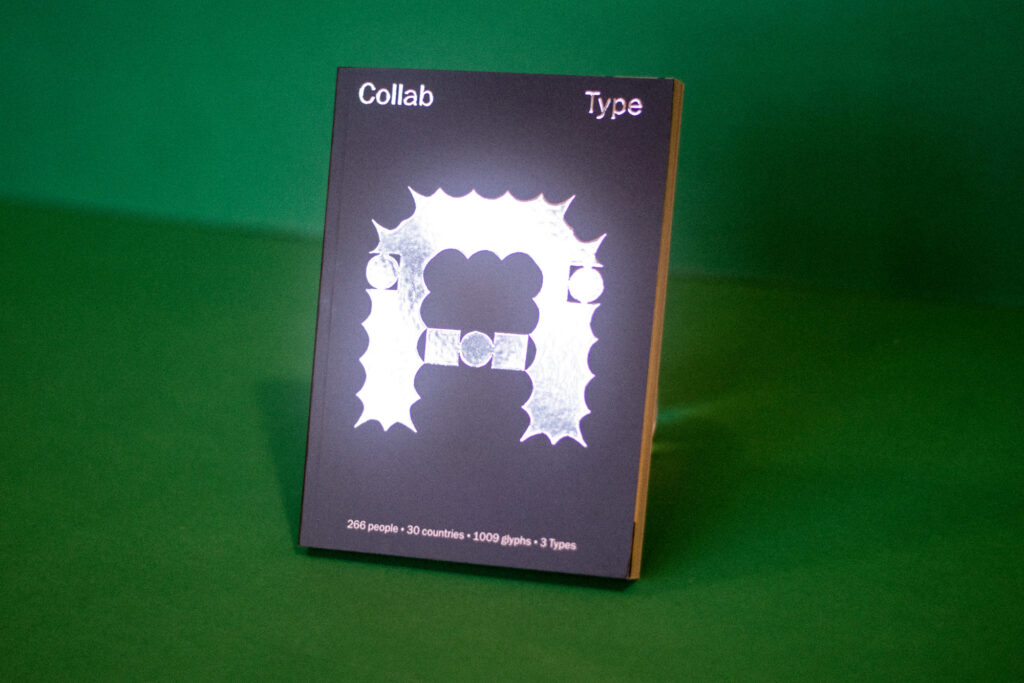

Secret Riso Club (GG): When we speak [with the artists] about the publication, where we want it to live and be seen, we gauge the desires of the group and consider how the project will best communicate its message. For the upcoming book Collab Type we’re working on, I want to put the money toward making a higher-quality object with a foil-stamped cover, and all the fancy stuff, because I feel like the project deserves it in some way.

Secret Riso Club (TR): Where do we see it circulating, and what should the physical experience of it be? As far as edition size, it's generally just a question of what we can afford where we are still getting a good deal and a high quantity? We also don't want to be sitting on copies of a book for a really long time, so then the question is: How can we push the sales? We do try to think of marketing—like with Collab Type, we're doing a bit of a larger edition, in part because a much larger group of people was involved in making this project, so hopefully a wider audience will purchase it.

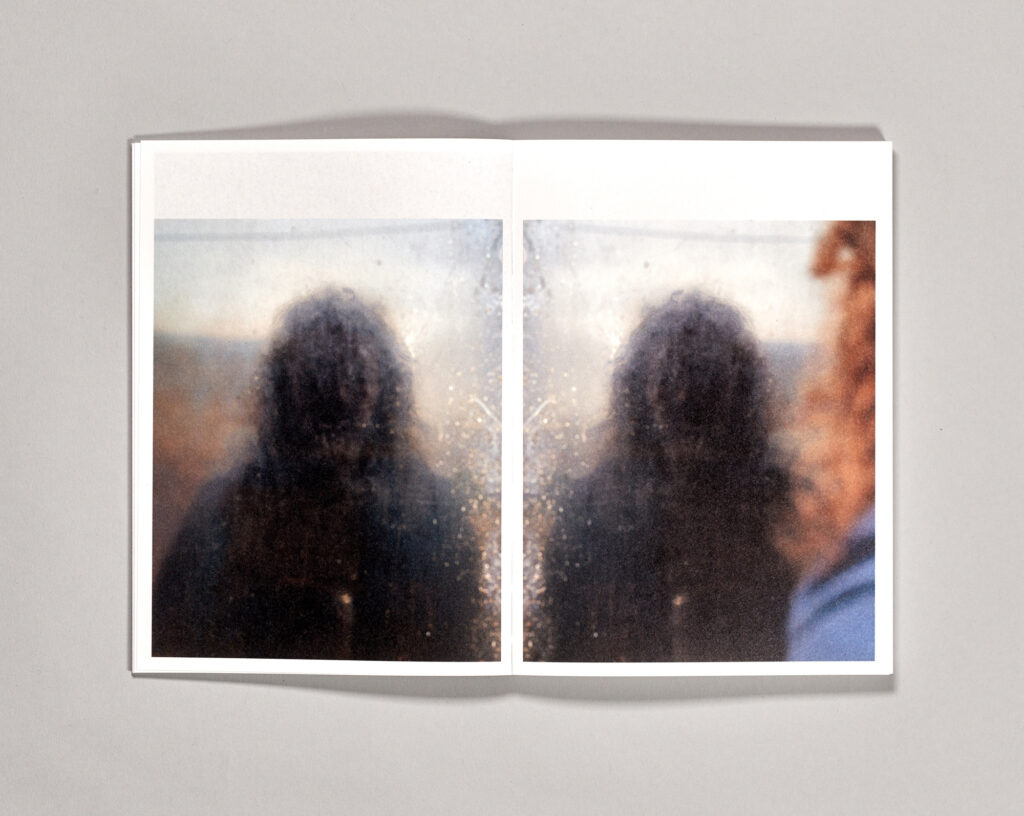

Gnomic Book: The beginning of any project is almost always a question of what is right for this project. For example, Shane Rocheleau’s second book, The Reflection in the Pool (2019), is made up of some older work that he had created with a group of homeless men living outside Richmond, Virginia, from 2011 to 2013. Early in the project, we wondered: What should that book look like? And at the same time we were beginning that book, there was another artist making a project about homeless issues, but her project was a large hardcover book. She was selling large prints for a lot of money to fund the production of the book, and something about that didn't feel appropriate to the issue of homelessness. It felt somewhat exploitative to me as we were thinking about how to do Shane's book, which should definitely be small and not have a hardcover. It probably shouldn't have coated paper, and it's going to include all these intimate little objects: a small handmade print, a handwritten letter from a homeless man to his mother from when he was in prison. Things like that greatly influenced the tonality of the book, and that's where we begin in terms of trying to think of how a book should feel and what aspects to spend on. If it deals with issues of corporatism, is it interesting or appropriate to mimic some of that language in the visual language of the book form? And of course, as the book gets larger, it gets more expensive.

For me, there is always a question around where you print. We've always printed in Holland because the quality of the work is superior. The Netherlands has this amazing generational history of bookbinding and of knowing what makes a great book, and not adhering to ideas for tradition's sake, but always trying to push the technology. So that's where I would love to print every time, but there are other places you can print for thirty to forty percent less, so it’s not always an option.

Flying Fish Press: Every project is different, and I do editions partially for financial reasons because there's no way it would make sense to do one copy of a letterpress project. I used to make editions of one hundred, but it turns out that because my work is so labor-intensive and takes so long to put together, it ended up becoming a problem—because we're still putting together some of these editions from fifteen years ago. Now I usually make editions of fifty so I can amortize the income over fifty copies, and I can do what's realistic based on how my work exists in the market.

I've noticed that a lot of people's prices have been going up, but I also feel like libraries have limited resources. Eventually, if everybody's prices go sky-high, libraries are only going to be able to buy three books a year, and who's going to get those sales? It's better if everybody has a more realistic pricing scheme so that more people's work can get into collections. Of course, I have no control over anybody else's decisions. But I'm going to do what I've always done, which is to come up with what I feel is a realistic price that will actually work for me. I wanted to also put in a word for the dealers because some people feel like the dealers are taking too high of a percentage, but I don't feel that way because they're out there selling the books. I don't have time to do that, and I decided early on that I wouldn't do that. I've always had really good relationships with my dealers because I'm genuinely grateful to them for taking my books out and selling them to libraries and then collecting payment. I really think that they're providing a really important service.

How do you consider in-kind resources that you add to a project? In-kind resources are value that you add to the project that is not a cash exchange. It could be your time as a graphic designer, your knowledge as a printer, access to equipment, and so on.

Secret Riso Club (TR): One of the in-kind resources we provide is a work exchange program. A traditional internship would often mean not paying somebody, which feels like a one-way street, and we wanted to keep it open so that people who had to work another job or are in college could learn how to interact with riso. The main component of that is that they need to propose a project that we then help come to fruition utilizing our resources and our platform to sell. It's been a learning process trying to make things equitable and collaborative.

Secret Riso Club (GG): Sometimes it’s difficult to navigate because we don't want to take advantage of anyone. We try to be super clear about our intentions and to give space for others to use, create dialogue, and give feedback.

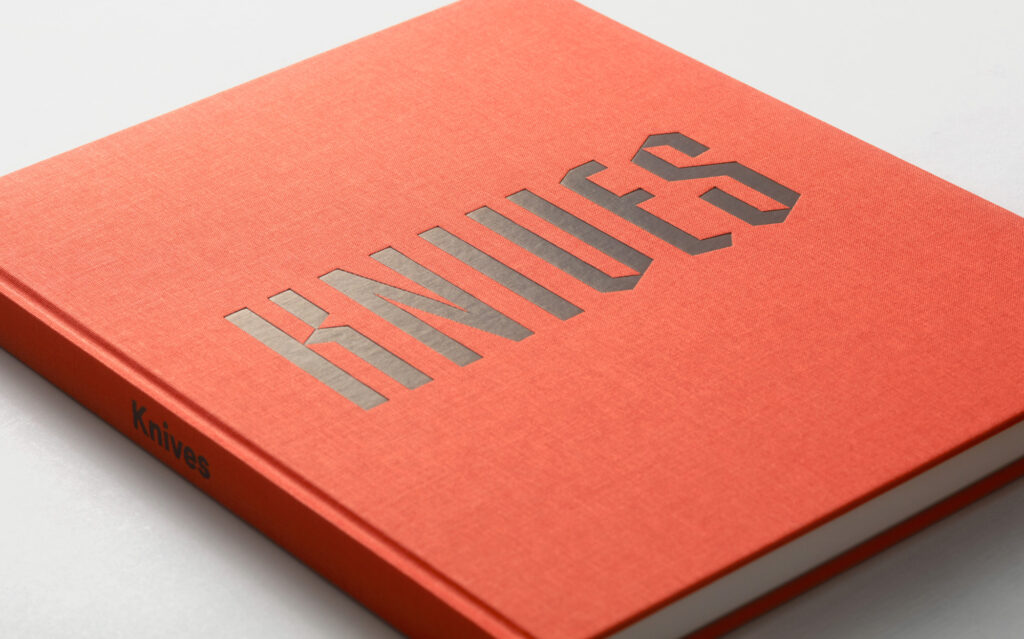

Gnomic Book: When I made Knives in 2017, there was a huge learning experience in terms of mastering the images for exhibition prints, and then taking those mastered images and doing my own lithography to convert them for the book. It did cause problems further down the line because it made me believe that lithography is not hard. The next time I did my own lithography, it was a disaster. These days we work with very talented lithographers, but it requires that everyone understand the process and why it has financial value. If you don't understand that, you might spend ten thousand dollars making a book where the lithography is totally wrong, and that's a huge loss.

As a small business owner, I do what I do because I love it, and the thing I like least about it is bookkeeping. The last thing I want to do with any artist we work with is try and deduct some percentage of each [studio] cost from the profit. That’s why we try to keep our model as streamlined as possible—because I don't want to spend eighty hours doing bookkeeping. I've been running the business on the belief that that's OK because you spend the rest of your life making decisions for financial reasons. Let this [my projects with artists] be my little walled garden, where I can find people who I share passion with and work with them.

Flying Fish Press: When I'm pricing out a book, I calculate machine time as a cost. For instance, I've had a laser cutter in my studio for twenty-two years. And when I bought that machine it was because I had the opportunity to use it as part of a long exhibition where they gave us a digital lab, and there was a laser cutter. I couldn't go back after that because my brain just kept handing me ideas that involved more intricate cutting than I could do with scissors and a knife. I had to look at my overall resources and make decisions like: I can drive a really old car because I really need this machine. When I calculate the price, I'm calculating a certain amount of time per copy spent on that machine.

Does the future retail price of the book factor into how much money you might invest into a project? Is there any kind of forecasting of how the book will sell?

Secret Riso Club (TR): We’ll usually calculate how much we need to make back to cover all the production costs. We don't really want to sell a book wholesale until we've covered our costs since the margin is lower, and we do think about the price as we're producing a book.

Secret Riso Club (GG): We don't want to produce books that are too fancy because then we'd have to sell them at such a high price point that it's not accessible anymore.

Secret Riso Club (TR): The pricing thing has definitely been something we have both learned, myself especially, as an artist and as an entrepreneur, I'm learning to value my work more. And honestly, raising prices to accommodate that hasn’t hurt our sales at all. Secret Riso items are still relatively affordable; we're not trying to sell a book for $100. Our favorite way to sell is definitely book fairs, where you're able to be face-to-face with someone and explain the project and the context, and you're not having to explain the price because they understand it, in a way. Then they have some connection to the project from the exchange.

Gnomic: Our threshold is that we sell it at twice the cost of production, which is deeply stupid, because if we sell it in a store then we make zero dollars on every book sold (since bookshops often take fifty percent of the retail price). And with wholesale, sometimes there are issues where, for example, if we sell on consignment, sometimes the stores won’t be able to return books that they haven't sold, and then it’s a loss. But I can't in good conscience make books really cheaply and then sell them for a lot.

It's always wonderful to see books (especially ours!) that people have had in their collection and cared for for a long time, still functioning as it was originally intended with long-term value. What’s challenging about the business model is that we make little money when we sell a book, but the hope is that we help develop artists' careers. For example, we made the book Half-Light (2018) with an artist in Tehran, Shahrzad Darafsheh. It was a total gamble; we happened to find her on Instagram, and I don't think she had a significant following at that time, and now—I hope in part because of our project with her—things are really taking off for her. And so that's a value that we provide, but it's also a value that doesn't necessarily come back to us in the sale of a book. The flip side of that is that now that technology is what it is, it's much more accessible for artists to make books at every level. Sometimes I can get a bit fatigued by just the sheer quantity. I would rather have more quantity and more quality.

Flying Fish Press: Forecasting is always tough, because I have made mistakes on that front where I've had editions I thought were going to sell really well that didn't, and vice versa. A lot of my work goes into public or institutional collections, and so it really depends on what librarians feel is important for them to collect at any given time—and also what's happened to their budgets, especially since the pandemic.

I feel like I have a committee in my brain that has to argue it out. One person is the artist who has the vision. And then there's the production-person-me who says: We need this to make it a reality. Then there's the accountant-me who says: You don't have the money to do that. And those factors in my mind are duking it out, and sometimes the artist wins, and sometimes the banker wins. But sometimes the artist does win, such as with a recent book of mine, Wayfinding (2019), which I ended up spending a whole extra year working on. I could have pulled the plug after the first year. But the artist was able to convince the committee that we needed more time; we've already invested this much. It worked out in the end. I was happy with the piece, and it was a very expensive piece to make, so the price reflected that. But it's still selling fairly well. So it's paying its way.

Also, people should realize that the price of the book does not necessarily reflect the profit. You can have a modest book with a bigger edition that's going to turn a bigger profit than a really expensive book will. I'm always looking at the margin and asking what the market will bear in terms of my pricing, which is forecasting. But I'm always nervous about pricing something too high and pricing myself out of my own market; everything in artmaking is kind of risky.

How much do the sales of the products you make sustainably fund your production and income?

Secret Riso Club (GG): Secret Riso Club is a full-time job for me, and it's providing a consistent income. I basically take all the income that comes from the studio through the different projects: sales, fairs, workshops, classes, and printing, and sustain the project using those funds. They allow us to produce new material, begin new collaborations, get new machines, and think of projects.

Secret Riso Club (TR): I've just moved to part-time this year with my job, and spend more time at the studio making work, which is a part of our conversation, too. Secret Riso has provided enough to sustain one person's income. How can we make it do the same for two people? It’s been a lot of brainstorming.

Gnomic Book: We just did an institutional project called On the Line: Documents of Risk and Faith (2022) by Makeda Best and Kevin Moore that we're really excited about, alongside a show at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center. That book is really ambitious, so it paid a little more than your typical artists’ monograph might. I also have Gnomic Inc., which is a design and marketing consultancy. My grand hope is that making the books attracts the types of clients that Gnomic Inc. would service. But I think the reality of corporate procurement these days is that Gnomic Inc. does consultancy work and Gnomic Book is fairly separate. But nonetheless, Gnomic Book is only possible because of Gnomic Inc.

Flying Fish Press: I have a full-time job outside of the press. I've been a professor for many years, and the press has really only managed to pay me half of a living wage in the Bay Area. For the last thirty years, I have paid myself a salary. That means I get the same amount whether I'm making a lot or whether I'm making a little, and sometimes people have heard the word “salary” and find it impressive. I pay myself a salary as if I was working at a grocery store, not as if I’m an investment banker. But that smooths out the budgeting process for me because I can see when I have more cash in the account that's going to last a longer period of time, or if it’s going to cover that period of time when I'm developing the next book, and I'm not necessarily pushing out a lot of orders. I may work sixty hours one week and thirty hours the next week, but I'm getting the same small amount every week, and that's helped a lot. I have also not applied for grants because grant writing takes a lot of time. Also, I don't want to lose any control over what I'm doing so I’ve made the decision to sink or swim on my own.