Interview with Ramyar Vala

May, 2021

Ramyar Vala (b. 1986, Tehran, Iran) is a multidisciplinary artist and designer living and working in New York. Ramyar’s multi-disciplinary practice explores the inner lives and circulation of traditional motifs— tracing how they travel, transform, adjust, and disappear trans-nationally and trans-culturally — through sculpture, installation, and video. On the occasion of Out of Sight, Beyond Touch, Maryam Ghoreishi and Jenna Hamed interviewed with Vala–whose sculpture was featured in the exhibition reading room–to further explore the interconnectedness among his multitude of craft practices.

Maryam & Jenna: Would you give us a brief introduction to your background? What contributed to your shift from graphic design to sculpture?

Ramyar: My practice began as a graphic designer at a studio in Tehran, with designing posters and exhibition materials within the art scene in Tehran. Because of my involvement in the arts I became more interested in challenging my own ideas instead of meeting the expectations of clients. Although, I am grateful that my journey into art stemmed from graphic design and the tools it provided. As a graphic designer, I had to find various solutions to promote an event or cause and for that I had to familiar myself with different visual techniques through research. But the shift happened during my time as a graduate student in the Art Department of University of Chicago. There, I was exposed and privileged to have access to a well-facilitated wood/metal shop. It took me around two years to start using wood as a medium. So, the discovered obsession with wood in Chicago redirected my practice toward sculpture.

M&J: The creative and production process designing wood and ceramic sculptures seem to be so widely varied–– each discipline activates the body and hands in different ways, and requires different tools. What influenced you to expand your sculptural practice to ceramics? How do you see each discipline influencing the other?

R: My recent research on the pigeon towers in the Middle East drew my interest in learning about clay as a material which likewise wood has been used in various productions from heavy constructions to furniture or small daily objects such as mugs, dishes, pitchers, or vessels. Both like any other raw materials require a close contact by the builder to be shaped into an object whether for use or contemplation. Both trigger a set of muscle memory required for grabbing, pushing and shaping. And of course, both come from nature.

The two are different in terms of handling and treatment. While wood necessitates patience and precision, the clay necessitates attention and care. The two are different in nature but in my practice they are complementary. This transition from wood to clay or the other way around is not only a physical progress but a mental shift. One needs to prepare the mind for invisible measurements unlike the precise measuring system in working with wood. Through memory one builds on the sensory touch of hands when working with clay. After a while it is possible to close the eyes and throw precise shapes on the potter’s wheel if this memory is well practiced. But the same with wood is not wise and could even be hazardous, as it requires a different kind of connection.

M+J: It seems like your work displays a cross between functionality, design, and visual art, which are some of the qualities of bookmaking practices. Seeing that your Sculpture The Bird in Love is currently installed in the Center for Book Arts reading room, functioning as a bookshelf, bench, and a sculpture, how do you as the artist understand this work fitting into the space? What other spaces do you imagine your wood sculptures to be exhibited in?

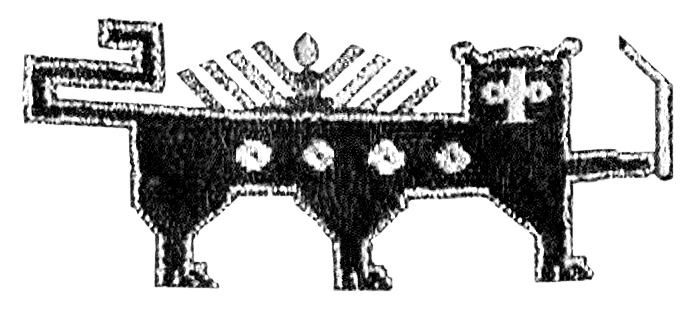

R: The pieces are tangible in a sense that they function as seats and containers assisting the flow of an exhibition. Each piece is inspired by a rug motif––similar to rugs in which the motifs represent a two dimensional space or a story, my furniture pieces include a historical reference and a story. The rugs are the heterotopian image of gardens on which the act of living takes place. And for me the sculptures extruded from these motifs are objects with which one continues the act of living. A book has a similar tangible function. It consists of a front and a back cover that include texts and images. It needs to be picked up and unfolded to be better understood.

I imagine my work to be represented where roaming, focusing, contemplating and resting is required. The sculptures are of material coming from nature representing the image inspired by nature for indoor spaces lacking nature.

M+J: Seeing that the exhibition is premised on the relationship between sight and touch, how do you think about the sensory experience when creating your sculptures, especially the works with functional qualities?

R: So much of what we experience as art when exhibited are solely objects to be in sight and looked at. The commodification of art has made it to be in such a way preserved. So touch seems to be the action that shortens the lifespan of art. I imagine my sculptures already having an ephemeral being as any other object that is in constant relation to being sensory experienced.

If a thorough investigation of eyes combined with gentle or rough touches of hands build an experience as a sculpture, I think it is important for the viewer to observe the surface, edges and textures of my work not only by sight but also by touch for a better understanding.

M+J: Can you further describe your research process designing your wood sculptures and ceramic objects?

R: Each wood sculpture starts from a motif I encounter on rugs. After each encounter or finding I study its form and look for the available historical texts or literature related to the motif. Let us take a cypress motif as an example: in my research process I have come across stories in various cultures, and from different origins related to cypress trees generating the same motif earlier or later. This takes me to trace the motif in other design fields such as architecture. And this allows me to learn more about the timespan a motif was formed over, the meanings it gained or lost over time and the new possible forms it can morph into.

The reason that I like using plywood is the visible layers of woods glued on top of each other. Such layering highlights aging, I believe. I modify this layering by adding more layers to a piece or by sanding down the layers in order to reach the surface of a lower layer which itself has a unique and unexpected texture.

And the reason that I use clay does have to do with its historical significance and its functionality in the everyday life of human beings. As I was working on bird motifs I came across written texts and architectural plans of pigeon towers and the benefit of pigeon’s droppings in farming . So in an attempt in collaboration with my brother, Rambod Vala we made our own rendition by using clay, the same construction material for building these towers.

M+J: You create structures that hold books, to create an intimate space for people to experience, do you think about the object of the book (including artists’ books, reference books, etc.) as sculptural objects?

R: In the sense that an object such as an artist book is not usually hung on a wall and that it occupies a three dimensional space, I think about books as sculptures. And since in my own practice I create objects that call for a more intimate attention, the same as for books, I think of books as sculptural objects.

M+J: In terms of the way you understand art to be commodified, and seeing that your artwork is to be experienced through handling, what are your thoughts on the way your artwork is handled and cared for when exhibited in public space? Is there a barrier or trust established between the artwork and its audience?

R: A carpet back in the day was an inviting surface for communication and as I mentioned before for the act of living. Whether we call a carpet a design or an art piece, it was where human relations would take place. Of course any spill or damage would worry the owner/creator of a carpet, but at the same time any incident was inevitable. I look at my sculptures the same way. So any audience interaction is part of the sculpture’s existence in a semi-public space like a gallery. For sure, I am not considering the possible intentional damage that may occur but any appearing sign of usage, I believe adds another layer to the aging layers of the materials I use.

M+J: Can you talk about the gallery spaces you’ve exhibited your work in, and what conditions you established for audience interactions (for example: handle with care, do not touch, etc.)?

R: The questions I had about phrases such as “ Handle with care!” or “Do not touch!” came to a better resolution for me when I was exhibiting the cypress of Kashmar at Grey Center at the University of Chicago. An attempt to bring the audience face to face with one of the social and political stories of a cypress motif, a medieval story that was entirely and deliberately neglected. During the exhibition, the audience was facing an entire floor piece covered with texts and motifs of saw dust in a big hall. It would take the audience a moment to interact with the piece and think of how to access the text. The audience was encouraged to walk on and through the installation of a written story in sawdust. Some would carefully walk through so the text is not ruined. Some would stay where they were by either being respectful to the piece or fearful of damaging it. And some others would take their steps on the text which would cause defacement of the work. This experience encouraged me to develop my sculptural furniture pieces with more emphasis on the relation between art and the audience in a gallery presentation.

M+J: Have you thought about your work in relation to the archive, which operates on notions of care and preservation for longevity? Are you building an archive of your sculptural and ceramic works? If so, what does that look like?

R: My sculptures are heavy and require a big space for storage. Preservation of such objects is costly. My only hope is to have enough of documented photographs of each object before its probable death. It reminds me of all the museum kept objects in Iraq that no longer exist physically but only in books. So, a book seems to be the kind of archive I will build.

M+J: Have you entertained the idea of creating an artist’s book? Can you leave us with an idea of how you would imagine the book to be constructed? What materials would you experiment with? How would you want it to be constructed? Considering your entry point into visual art was graphic design, how would you bring the craft of graphic design into the design of the pages? R:

R: As part of my collaborative project with my brother, Rambod Vala about the pigeon towers we are developing the design of a book that includes our research, process, design, and a history of such towers. We have different ideas of how the binding should be in order to make the book shape a vessel itself and to stand on its own body. But still there is a lot we have to figure out as we are in early stages of this project.

All images are courtesy of the artist, unless otherwise indicated.